The India Company and the island of Réunion - pt. 1

Another anthropological treatise on Réunion

While researching other topics I came across a French website collecting numerous essays, letters and conference transcriptions on the topic of anthropology in the countries of the Indian ocean, more specifically how the French state and its institutions impacted local customs, laws and demographics. Since I love learning about the topic of the island of Réunion I thought I’d take the time to translate it in English, since I’m reading it anyway. It’s quite a large series touching on 17th and 18th century law and economy, demographics, climate, etc. I’ll probably have to split it into 5-10 pieces.

This introduction lays the theoretical and conceptual basis for the early colonial economy and details how the managers of the colonies, as well as the authorities back home, considered these new territories. My previous translation from last summer of another document on the colonisation of Réunion is a good companion piece to this one.

The contents of the website are, as far as I can tell, “copylefted”, meaning the author allows use and distribution of the contents. It seems mr Bernard CHAMPION is to be credited for the website, which can be found here. Pictures will be added by me for illustrative purposes, and credited individually as required. All text formatting is preserved as-is unless stated otherwise.

Introduction

In his manuscript on the peopling of the island of Bourbon, “Birth of a christianity, Bourbon, from its origins up to 1714”1, Father Barassin writes: “We might be criticised for having tarried in a time period from which the island of Bourbon is almost completely absent and for focusing overlong on Madagascar. This is not without a very specific goal. It’s because in this time ‘Madagascar and the Neighbouring Islands’ form a single whole; afterwards the development of Bourbon, first as an extension of the Great Island, then as a French base with the aim of future colonies, has been for the entire XVIIth century dependent on Madagascar; it’s most importantly because the colonising ideas formed in this time, especially by Flacourt, and especially on the influence of the religious element, will have repercussions on Bourbon…” (1953, p.3) (emphasis ours).

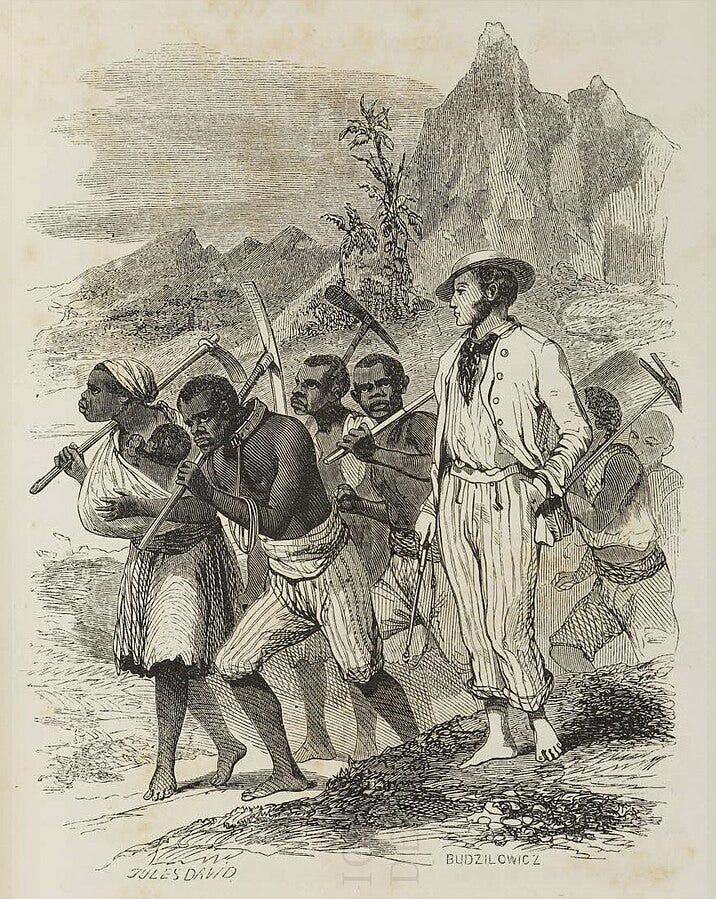

The first French attempt at settling Southern Madagascar ended in failure. This attempt nevertheless constituted the first test of jurisdiction with the aim of exploiting colonies on the road to the Indies. In the program that Flacourt affirms to be putting in place, in the colonisation plan drawn up by the company in 1664, in Mondevergue’s instructions, in Jacob de la Haye’s decree are found expressed the the economical philosophy and legal tools which will dictate Réunion’s history. A dual society, the product of feudalism, carrying out for its sponsors the production of colonial perishables for the European market and following as law the exploitation of the cheapest labour when the world was within reach, the island’s history is a concentrate of the types of enslavement that Man can impose on his fellows and offers a glimpse on the processes of social differentiation founded on interest, under the meaning that this word takes within companies of trade and which will be trivially expressed in the philosophy of anonymous societies2. Referencing Benjamin Nelson’s book on interest loans: From tribal brotherhood to universal otherhood ("in modern capitalism, all are 'brothers' in being equally 'others'" - Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1969, p. XXV) and the change that was made to the West’s history by Calvin’s economic theories (the values it legitimizes), one can’t help but notice that “universal otherhood”, the anonymous fraternity of the anonymous society, turns out to be a universal indifference likely to unrealise all types of denial of Humanity. Colonies are thus world where interest - the fourth order3 - is seen to be optimally put in place in “new” countries, new meaning that those involved in interest run everything: men, goods, means of cultivation, acquisition of harvests, and the sale of goods, as well as the law which dictates the whole thing. Réunion’s history is the culmination of such a calculation and the diversity of today’s Réunionese population is the living picture of this colonial history: the first “inhabitants” from Europe, the slaves deported from Madagascar and Africa, the wage workers recruited mostly in India, starting before the abolition of slavery but on a whole other scale after abolition.

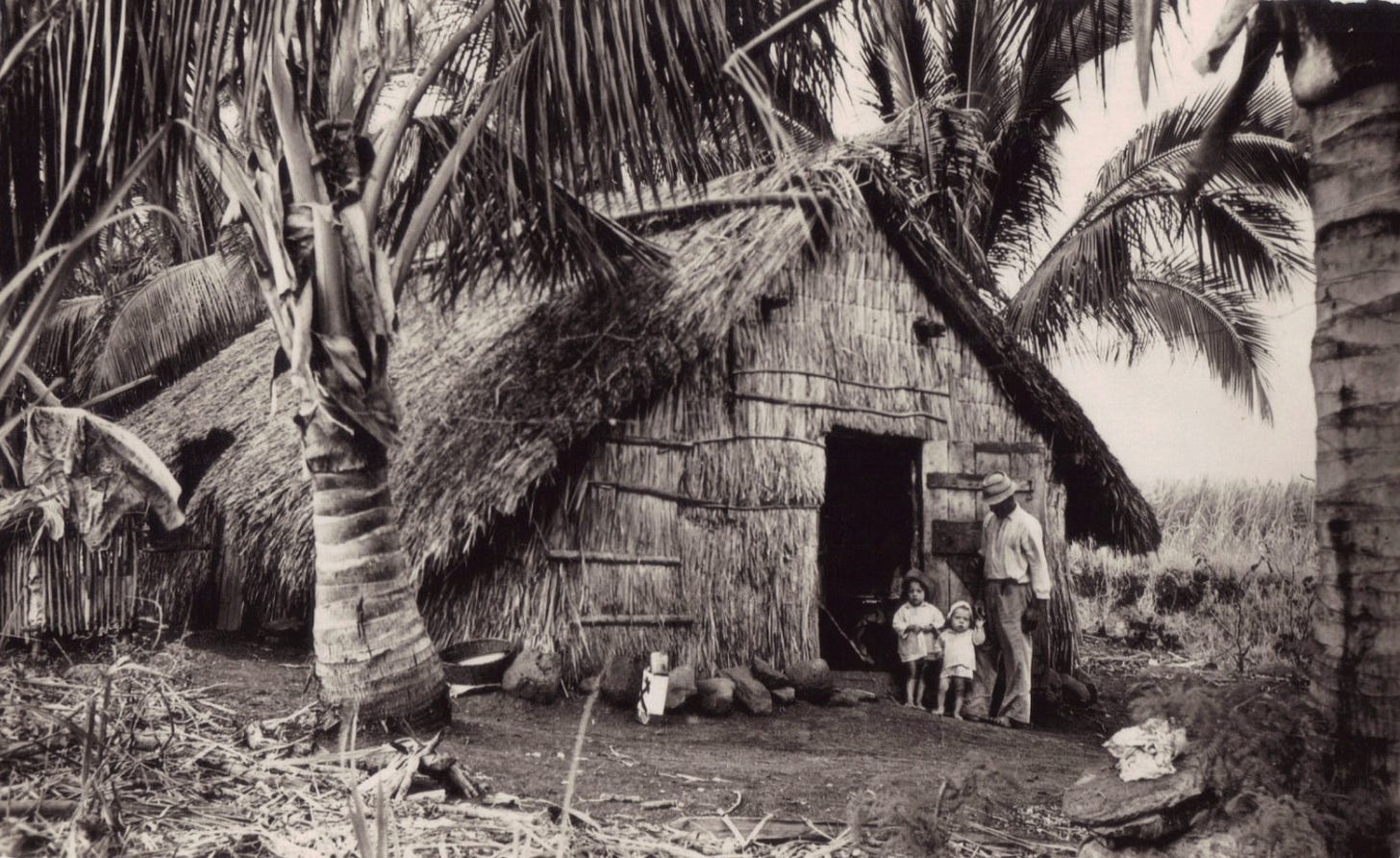

“One only comes here to make money”, notices Girod de Chantrans at Saint-Domingue (Journey of a Swiss in different American colonies during the last war, Neuchatel, 1785, p. 236) 4. Making a fortune in the islands and going home to Europe, or making a fortune in the island from Europe… In Réunion, observes Louis Simonin in 1861, “men are entirely focused on enriching themselves as quickly as possible. The sugar is their golden calf and everything not related to it is worthless to them.” (“Journey to the Island of Réunion” from 1861, published in Around the World - Edouard Charton, Hachette 1862)5. “Always looking for a speculative crop which would quickly allow them to amass a fortune large enough to return to France, one author comments, the great Réunion colonists started sugar cane plantations.” This coexistance of two separate worlds, “the interested” and the doers, where humanity is subordinate to usefulness, is foundational to Réunionese society. From the onset, the “lords of the Company”, their representatives or their successors, enjoy a position of monopoly and domination. In the time of coffee, “in 1731, writes Jean Mas, the four strongest producers […] are Justamont and Dioré, previously governors, Dumas, governor, and Feydau-Dumegnil, member of the High Council.” (Mas, Jean, “Property rights and rural landscape of the Island of Bourbon - La Réunion”, PhD thesis, University of Paris, Faculty of Law and Economic Science, 1971, p. 36)6 Pierre-Benoist Dumas, executive officer of trade in the India Company, acquires for himself in one year property estimated to cover 885 hectares (see: Quarterly collection of works and exclusive documents for use in a history of the French Mascareignes, t. I, 1941, p. 1-20)7 . Sugar production then produces such a concentration of wealth that two landowners “Kerveguen and the colonial land fund own between them about half of the island’s lands” (Mas, op. cit., p. 9). In 1914, governor Cor declares “… three landowners alone, based in Europe, pocket half the profits from the exported goods derived from the main crop, sugar cane”. (“Pauperisation in Réunion”, Official Paper and Bulletin of the Island of Réunion, 18 December 1914, p.475.)8 . - Today, as shown by the yearly reports of IEDOM (Institut d'Émission des Départements d'Outre-Mer), the near-total value of the public money transfers that feed the Réunionese economy is expatriated as private transfers.

Réunion’s present history is dictated by the conditions of its founding. The tropical island, a testing ground - not just in stories- for social and religious utopias, is also a closed field of the exploitation of men. As soon as tropical productions lead to notable profits, islands, terra nullius, closed and far-flung spaces, virgin or emptied of their inhabitants, likely to be granted rights to exceptions beyond the eyes of the Métropole9 - “I believe, writes the Lazarist10 Lebel, that we would have done better to stay in France than to come so far to […] learn of things we should have remained ignorant about”; “… one is put in irons and chains. Isn’t this a nice mission and a nice use for missionaries? One would have to be quite a Doctor to convince me that one can gain heaven through this profession.” (Recueil Trimestriel..., t. III, p. 253 et 254)11 - become a stage where ramshackle enterprises will supplant utopia. The Eden of the first travellers and of repentants seeking a confessional haven is also the Devil’s island. A syndicate of “interest havers” thus invents remotely an economic model which will result in a deportation and movement of populations without precedent. Monoculture and monopoly, the “island-colony” makes plans with land, men and machines as if they were of the same nature. When “progress” will have made obsolete this form of extraction of labour known as slavery, the relinquishing, on this economic wasteland, of the passive actors of this wealth-creation will be the common fate of all the “sugar islands”. Slavery, to quote Schœlcher, is a plague upon masters rather than a fault of theirs; the fault is with the Métropole, which ordered it and initiated it (Des colonies françaises : abolition immédiate de l'esclavage, 1842, Paris : Pagnerre, p. 260) . By pronouncing this judgement, Schœlcher aimed to absolve the masters, collective responsibility is also involved in the torturous destiny of the slave population after 1848. Today’s sociology is the product of this history.

The “inhabitant”, the legal status of the colony

On the 4th of August 1764 an edict is published, reporting the acquisition by the royal trust of the îles de France and Bourbon. Until then, the islands, ceded “in perpetuity with all ownership, law and sovereignty” are under the rule of the colonial pact or exclusive system. The concession on “the Island of Madagascar, also known as Saint-Laurent with the nearby islands… so that the Company may enjoy it in perpetuity with all ownership, law and sovereignty…” describes a fiefdom. The managers of the Company are those lords of the aforementioned islands, exercising sovereign power on the land and the people. The land ceded by the Company is ceded “for use as a commoner”, in exchange for paying taxes to one’s lords. Land taxes, imposition in kind and corvée labour12 (tasks which, on Bourbon, were carried out by the slaves of the contractors).

Auguste Billiard - Journey to the Oriental colonies… (1822)

“In obtaining the privilege of India’s trade, the company was vested with all the rights associated with the titles of lord and master of the lands it was ceded; no gentleman was ever more jealous of his prerogatives: the colonists only owned through emphyteusis, forced, at every transfer of inheritance, to pay rents to the lord under the barbaric name of lods et ventes. The company, which chose the crops, received, at a price it fixed, the produce of the soil, and sold expensively to the colonists the merchandises it alone was allowed to bring them in exchange. It’s difficult in such a system, to reconcile the colonies’ interests with the insatiable greed of the company. (Auguste Billiard, Voyage aux colonies orientales, ou lettres écrites des Isles de France et de Bourbon pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820..., Paris, 1822, p. 263-264)

Pierre Poivre, charged with setting up the first structures of royal administration after the dissolution of the India Company, would free these lands from these practices “anciently drawn from the chaos of our feudal laws”, in his own words, “would free from any kind of servitude the lands of these colonies, which would now on be free like the brave colonists occupying them.” (id., p. 237).

The edict of the 4th of August 1664 is thus titled:

“We have given, ceded and granted, and give, cede and grant, to said company the island of Madagascar, also known as Saint-Laurent, with the neighbouring islands, forts and houses which might have been built there by our subjects, and as needed, we have subrogated said company to the previous one for said island of Madagascar, so it may be used by said company in perpetuity, with all ownership, law and sovereignty.”

The Company is a feudal lord which applies the land ownership system of censive13 , the valorisation of the lands being the judicial cause of feudalism. The obligation to cultivate is regularly cited in its correspondence. A royal decree given at Marly the 27th of February 1713 reminds “his Highness orders that those in whose favour contracts are provided are obligated to put said lands under cultivation in an appropriate timeframe, otherwise if this is not done beyond the given time his Highness wishes for them to be stripped of their ownership of the land, and these given back to the India Company to be distributed to other inhabitants under the same conditions…” The Company is also an “interest”, a legal person formed by the meeting of its shareholders, and its monopoly, of the type granted to guilds or corporations, answers to the new concept of “colony”: an extension of the crown, defined by a mixture of territorial and commercial jurisdictions. A “double customs” weights on the colony’s trade, imports as well as exports: the island’s produce must be sold in the shops at a price fixed by the Company, and the colonists must buy merchandises from these shops. The monopoly of the “king’s store” is thus added to the feudal tax and the obligation to cultivate. The type of commercial entity created by the Discoveries being without equivalent (foreign to the areas reserved to corporations: regulated and sworn trades), and involving territories where the principle of terra nullius prevails, with some exceptions, can only depend, in the laws of the Ancien Régime, from privileges (“leges privatae”), similar to that which allowed the creation of royal manufactures (privileged trades). The grant of commercial privilege and territorial sovereignty makes the managers of trade companies into lords in the feudal manner, the “lords of the Company” being, besides the traders, notables belonging to the great organs of state. The colony is thus a composite of land-based and trade-based feudalism. (The French Company of the Orient of 1642, founded by Rigault, thus counted among its shareholders five “advisors to the King”, Fouquet, Aligre, Loynes, Levasseur and Beausse.)

Colonies are thus areas with a commercial vocation. “The aim of these colonies, writes Montesquieu, is to make trade on better terms than what we do with the neighbouring peoples, with which all advantages go both ways. It was established that only the Métropole could negotiate in the colony, and this for one major reason, because the goal of the establishment was the increase of trade, and not the founding of a city or a new empire” (from L’Esprit des Lois, XXI, 21). Under the text for “colony”, the editor of the Encyclopédie, who signed MVDF (Véron de Forbonnais) develops that these, being established only to be useful to the Métropole, it follows 1° that they must be directly subordinate to it and thus under its protection, 2° that trade must be exclusive for its founders.” “Colonies would no longer be useful if they could do without the Métropole: it is thus a law derived from the nature of things that arts and culture must be restrained in a colony to such and such topics as is convenient to the dominating country.”

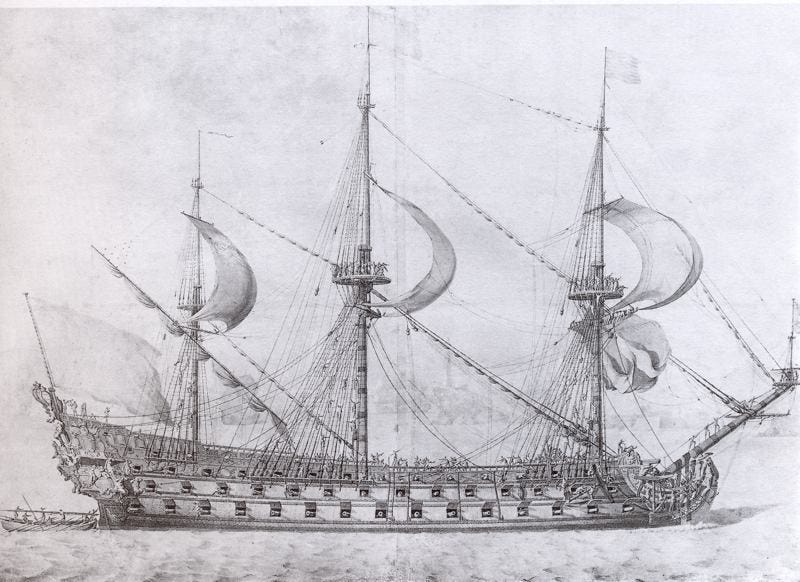

“The principle of the commercial legislation of French colonies of culture, writes Delabarre de Nanteuil in the article “Customs” of his Législation de l'Île de La Réunion (2° éd. tome 2, p. 300) has always been exclusive, that is to say, they must only consume French products shipped under a French flag; furthermore they must reserve all their produce to be shipped to France, by French ships. Such is the colonial pact.” Agent and benefitor of the colonial pact, the company is an entrepreneur. It befalls it to furnish the island with colonists and provide them with means of production. (“With regards to inhabitants, explains La Bourdonnais, - with some ambiguity - in his Memoir, the Company must drive them through an imperceptible and natural process to every aim which might be advantageous to it.” p. 65). Credit for one year of provisions, seeds, tools and slaves are granted to them. (lettre de la Cie au Conseil Supérieur de Bourbon du 23 décembre 1730, citée par Mas, op.cit., p. 38).

Lozier Bouvet to the managers and shareholders of the company

In l’île de France, 31 December 1753But before we think of making colonists, we need blacks to give them. It has been decreed at the general assembly of the inhabitants of Bourbon for the treaty of 1732, that at least eight slaves were needed to make a property profitable. That is to say three Axe Blacks, three black women, one black boy and one black girl14. The Company is informed of the work there is to do on these islands, to clear the land, clean it, plant, harvest and carry the grain to the store: and it knows that all this is done through the brawn of the blacks, with no help from industry. One black falls ill, the other goes marroon15, etc. With eight blacks an inhabitant can feed himself, his family and his blacks after one year.

A. O. M. Registre C4 7 (Aix-en-Provence)

It falls to the company to exploit the island according to its resources and configuration. “It’s certain that this island can only be advantageous through two means: because the cultivation of its lands or superficy can produce, or through the trade it can open, increase or conserve.” (Mémoire sur l'Ile Bourbon adressé par la Cie des Indes au Gouverneur le 11 février 1711 - Recueil trimestriel, t. V, p. 164). The Company thus defines the fate of the Mascareignes islands, ladders on the road to India, based on their natural attributes. For a time, Bourbon’s duty is to provide ships with “refreshments”. Turtles, whose exploitation is limited through interdictions on taking juveniles or “chickens” (hatchlings), as well as cows, pigs and goats (which breed free) are useful resources. There is, according to Flacourt, a single coconut tree on Bourbon (1661, p. 127), “which took root four or five years ago, according to what the Frenchmen living there told me”, but the land turns out to be fertile… Flacourt reveals, regarding Madagascar, “that this tree [Voaniou, the coconut tree], is not known here: but that through chance the sea threw one of its fruits on the sands.”

Conclusion

We see that early colonialism was marked by a rapacious greed taken to even further extremes than what we know today in the 21st century. These lands were purely sources of commodities to be extracted as efficiently as possible, long before more modern notions of nation-building, “civilizing missions” or extensions of imperial power and population numbers.

The next part will get down to the nitty-gritty of census data on numbers of colonists to Madagascar and Réunion in its early history: their origins, destinations, and the often unfortunate fate that awaited them. The early laws of colonial Réunion are also mentioned. Thanks for reading!

“Naissance d'une chrétienté, Bourbon, des origines jusqu'en 1714”

“Sociétés anonymes”, French term for a type of limited company, with shareholders etc.

A reference to the old theory of social organisation dividing society into three groups, landowning nobles, clergy, and everyone else.

Voyage d'un Suisse dans différentes colonies d'Amérique pendant la dernière guerre, Neuchatel, 1785, p. 236

"Voyage à l'Ile de La Réunion" de 1861, paru dans le Tour du Monde - Edouard Charton, Hachette 1862

Mas, Jean, "Droit de propriété et payasage rural de l'île de Bourbon - La Réunion", Thèse pour le Doctorat, Université de Paris, Faculté de Droit et des Sciences Économiques, 1971, p. 36

Recueil trimestriel de travaux et documents inédist pour servir à l'histoire des Mascareignes française, t. I, 1941, p. 1-20

"Le paupérisme à La Réunion", Journal et Bulletin Officiel de l'île de La Réunion, 18 décembre 1914, p. 475

The French homeland, which rules over all its colonies. Can be used to describe the government or France itself.

A Catholic missionary organisation

Actually I’m tired of translating these so they’ll just be left in French now

Similar to a tax, except the payment is not in currency or in kind, but in carrying out physical work

Yearly payment on land to a lord, from medieval times

You can guess what word he used here instead of “black”

Flees slavery. On Réunion these escapees would congregate in the densely forested and inaccessible “circuses” and plateaux at the centre of the island, living off foraging and possibly some occasional banditry, being periodically hunted by local police forces or garrisons.