Settlerpunk 1717

Corporate wage-slavery in tropical Réunion

Introduction

What a trip we’ve taken over the past few weeks of translated texts, from the founding of a French colony of castaways, orphans and slaves on a lush tropical island, to the elaboration of one of the most comprehensive systems of exploitation of labour near the equator. As each European country took inspiration from the others in developing exclusive companies of trade to manage the commodity production of far-flung territories, they all converged on a hybrid system using debt, monopoly and slavery to create a network of plantations where the masters were barely freer than the slaves.

Of course this wouldn’t have become possible without the introduction of “cash crops”: plants that couldn’t be grown in Europe yet were highly desirable on the market. There were crazes for several of these throughout the years on Réunion, but the first one, which cemented the plantation system that’d survive until the abolition of slavery almost a century and a half later, was coffee.

This final translated essay from https://www.anthropologieenligne.com/ (written by Bernard Champion) shows the tensions between long-time inhabitants of the island and European newcomers, who were generally well-off entrepreneurs come to make a fortune in the trade. We also see how the company, to ensure the smooth running of its business, made sure to relegate the settlers to the rank of second class citizens, “butlers” at the service of the “lords of the company”.

"Inhabitants" versus "Officers of the Company"; " Créoles" versus "Hiropians"...

The inhabitants, "a people, writes Lougnon, who were only distantly reminiscent of Europe" (op. cit. p. 17), new islanders, exploited by the feudal lords of the Company, define themselves as "créoles" when faced with "people newly arrived to the islands", described as "Hiropians" ou "Heuropians". Two memoirs, which answer each other and bear no signature, dated to the 9th of December 1726 and the 9th of March 1727 (AOMN, F3 208 and F3 206), allow us to judge of their condition - while the cultivation of coffee is ongoing - compared to the expedition of 1678 (vide supra). The first memoir is addressed to "your lordships of the Council of the Indies" and the second to "The Very High and Powerful Prince Monseigneur the Duke of Bourbon".

The inhabitants, "informing [the duke of Bourbon (while "praying him very humbly not to be put off by the bad quality of their writing")] regarding trade, the cultivation of coffee which will truly be in a short time the wealth of this colony", formulate their requests regarding the "tyrannies" exerted by "the governors, store keepers, and other officers" (assorted with threats of exile, banishment and confiscation of goods) and develop, they who consider themselves those best positioned to "make this island fertile and trade-worthy", a sort of audit of the colony and the colonial administration.

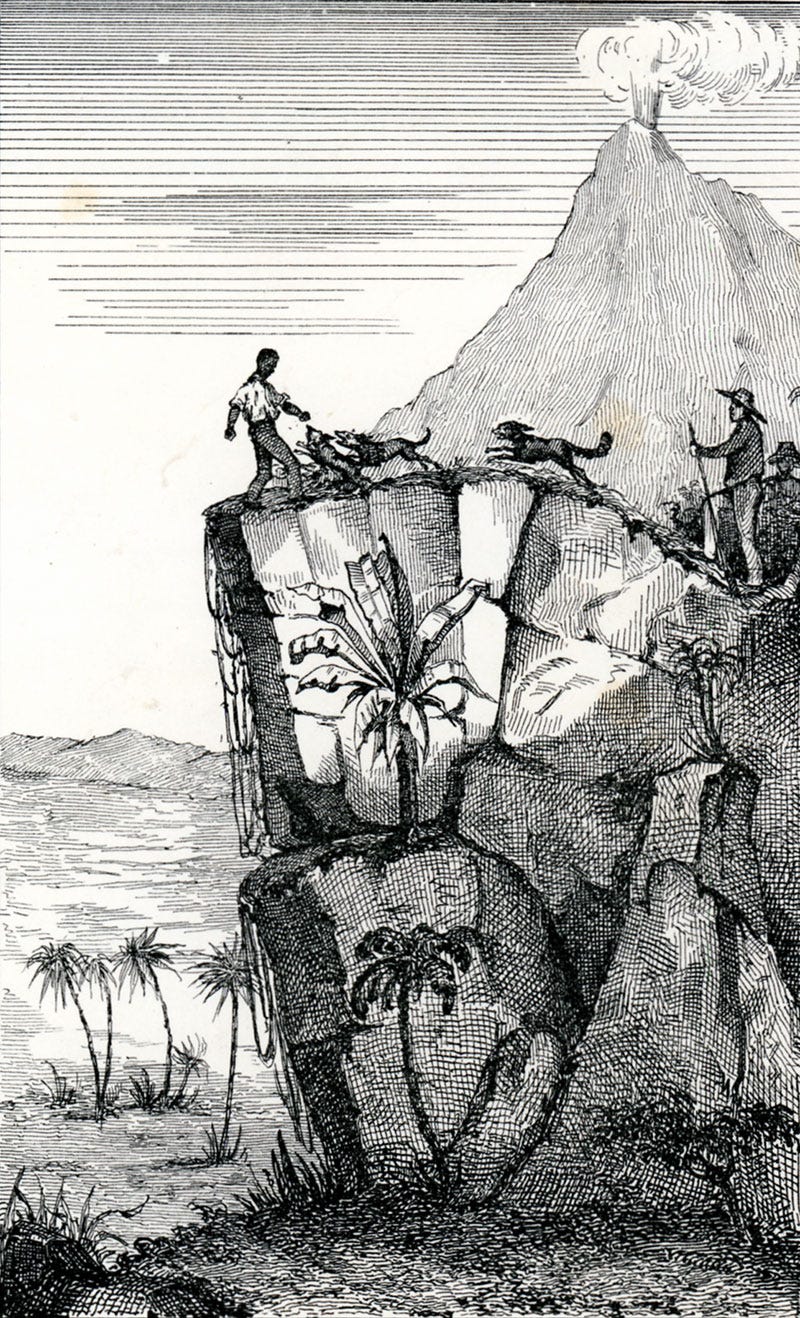

- First observation: the resources of hunting and gathering are spent and insecurity, which reigns in the island (the marronnage1), dissuades the inhabitants from raising cattle: "the isle isn't what it once was, supplies dwindle day by day, as there are neither turtles nor pigs, also what we raise profits us not, because of the mischief caused by the slaves there".

- Insistently pointed out, the "governors, store keepers, and other officers" of the company are the main actors of the injustice done to the créoles2 and the disorder reigning over the colony. "The deplorable state in which we are reduced which is in truth more pitiable than that of galley slaves through the tyrannies which are daily imposed on us by our governors, store keepers, and others officers of said island and the fear in which they have kept us, and keep us daily, threatening us with strong assurances that they claim are backed by the sirs of the Company, and the fear of exile they threaten us with, and they even have us endure them whenever we make the slightest protestation for our rights, making us abandon our poor families or sending us to l'Isle de France3, and threatening us with banishment and confiscation of goods [...]".

- One of the main complaints is due to the contradiction, pointed out by the inhabitants, that they must cultivate the colony and yet are refused the blacks necessary to this cultivation or that they are sold at "prohibitive" prices. The Company's officers thus grant themselves "blacks from the trade", leaving the inhabitants without manpower:

"It's impossible for the coffee to succeed so long as Messrs the governors, store keepers, and officers do what they do" "if your highness does not make a few allowances to those who are powerless to obtain slaves". "Our superiors [in the facts] make deals with the captains of the ships by buying their trade blacks two hundred pounds apiece, which said ship officers had bought in Madagascar for themselves, who, to hide their game, claimed to sell them to the highest bidder [...] said blacks were then pushed up to 300 coins by our officers, while they only cost 200 for the agreement they made with the officers of the ships." "When the ships arrive to trade slaves, they take great pains to take out all the best and [...] we are forced to have all the bad." The price fixed by mr. Lenoir4 "no one enjoys it but the sirs of the Council, and their associates, and some privileged people, the poor always pay the same price for them, only getting the lame and leftovers." "This last trade the blacks weren't sold at the fixed price. But estimated quite expensively for India pieces5, 350 pounds and the negro women also 300 pounds" (which were worth 150 pounds "more than 7 years ago") "we can't manage for ourselves at these prices". "But some have up to 60 others 23 and more", "there is no regard for the poor" who "need it the most". "We were told about five years ago that" they would keep "the India piece blacks at 200 francs".

In truth, the slaves are monopolised by the "feudals" of the Company: "there only being in the colony about thirty inhabitants" "who have the power to make commodities furthermore the greatest part are rogues who retired with money to this island"...

- Pointed out, in effect, among those responsible for the disorder: the "new inhabitants", the new arrivals in the colony, unjustly favoured at the expense of the créoles: the "Hiropians" or "Heuropians", or "rogues", precisely, retired with money to the island, who give nothing to eat to the blacks that they are provided and who are quite incapable of going out after the maroons...

"We had the sadness to see in this latest trade that blacks were given to people newly arrived on the island as well as land that was refused to twelve of us. Blacks were even given to people who owe more than 3000 pounds preferably over those who've been carrying the weight of the country for over 40 years, even those who wanted to pay on the spot" ; "we ask why the same thing isn't done for us, being the ones who carry all the burdens"... "they are given slaves and don't have the ability to provide for their subsistence" "and to do so, the slaves are forced to steal everything they find even to go in the woods, and then we're forced to go seek [them] at our own expense..." "We're the ones who shoulder all the burdens without being able to enjoy any recognition, to the contrary. If there is some allowance to be made it's made to those who arrive on the island." It's so visible that "some of our lands were confiscated to encourage their settlement."

- At last, the hoarding of the commodities sent by the Company by the officers and the "constant dealing of the sirs of the High Council" are also a subject of criticism and denunciations. "We go from the trade of the blacks to that of commodities that the company sends here to be of use to the inhabitants", "the store keepers, the officers chose the best and most beautiful for themselves to sell it at excessive prices"; "the choice of these sirs, then their privileged relations", the latter having "in appearance a permission to deal"... "Also all the commodities are sold to us at a high price" while they buy "ours at a low price".

The Company's "ingratitude" towards those who "carried the weight of the country" and "conserved the island" for its interests is obvious:

"We were very careful to conserve the island for our interests as well as for the safety of those who live there"

"Those who've been carrying the weight of the country for over 30 years"

We are "pained to see that there is no gratification made to Antoine Martin and Hyacinthe Martin his brother, from the pains and care they took to cultivate the first coffee trees that were planted in the island" "and if it's seen that today we are able to make a large production, they're the ones we owe it to" "far from favouring them in anything they were once again refused blacks from this latest trade for their money".

"For the past 20 and 25 years that we've been in a colony cultivating a house that was given to us from the Company which we justify with our contracts... [the Company's officers] finding them unprofitable, tear them up in the middle of the council... calling us Lazy, and Mutineers... Sending us to quarters that are neither inhabited nor habitable."

Instead of taking into account what the inhabitants are due, "without examining these things they are sure to speak to us in harsh terms, even to contemptuously reproach us for our poverty it's clear that we'll always be reduced to this point so long as no one will help us. Despite all this we are tirelessly gathering this year one hundred millier6 of coffee." "It's impossible for coffee to succeed as long as messrs the Governors, the store-keepers and the officers do what they do" "if your highness doesn't make some allowance to those who are powerless to get slaves"... The first inhabitants must be helped to "make this island fertile and trade-worthy..."

The council of Bourbon, in a letter from the 9th of June 1731, mentions "illicit meetings held by the inhabitants of the isle of Bourbon, without any authority or confession, under the pretext of going to France to carry complaints against the Company" (Correspondance, t. I, p. 133) and defends itself, in a letter from the 20th of December 1731, from the accusation of favouritism: "You say, sirs, it is retorted to the managers of the Company, that we don't seem to favour the humble inhabitants. Such was never our goal: but without depriving them of the allowances you wish to grant them, and of all the aid they need, we believed that, without miscarrying justice, a difference could be established between the master and the butler, and an officer and a soldier. A soldier, a sailor, becomes sick on a ship of the Company: were he to make himself an inhabitant, would he be given the same allowances, in blacks and other items, as we do to persons of a certain rank who, to develop a house, above and beyond the credit that the Company provides them, paid considerable advances out of pocket? Such are several of us, such as Sirs de la Farelle, Justamont, and several others. Five or six inhabitants of this caliber are worth more, for the Company and the colony, than a hundred others. What is the usefulness for the Company, and for the colony, of the houses that are barely able to feed their masters?" (Correspondance. t. I, p. 146-147).

The "créole genius" (Correspondance, t. II, p. 312) and the "Europeans", the Bourbon council version...

In a memoir dating to the 31st of December 1735 addressed to the Company (signed by Lemery Dumont, de la Nux, Morel, Brenier, d'Héguerty, Dusart de la Salle), the Council of Bourbon paints a sort of history of the colony and the respective contributions of the "Créoles" and the "Europeans" in its development - memoir which appears to be an answer to the accusations cited above. "The Créole, naturally indolent and buried in his ancient customs, it explains, has trouble dedicating himself to the cultivation [of coffee] whose progress he only sees from a very remote point of view, and wants to wait for the thing to be accomplished; the European, more enterprising, forges ahead, makes use of his blacks, and proves to the Créole that there is a true benefit to be hoped for in coffee; the latter wakes up, but a little late, and in the time that several Europeans, following the example of the former, having obtained the remainder of the lands that were to be ceded, and the families of the naturals of the island having multiplied, their houses and enterprises have seen themselves considerably diminished by subdivision. The European, naturally more active than these, instead of falling into this situation, wisely predicting that land would become rare, misses no opportunity to buy some with his own coin, whenever the opportunity arises to acquire some; proportionally to the increase of his property and cleared lands, the Council aids him." It's thus, conclude in their defense the Company's managers, that "a colony composed of people picked up from the four corners of the world, limiting itself to recruiting the bare minimum requirements, sees itself [today] considerably increased, entirely cleared [and] presenting a beautiful, good and well-policed province" (op. cit., p. 299).

The term "European" probably designs, both those named euphemistically "new inhabitants", the rogues retired from piracy and settled in the island with their booty and the immigrants attracted by the coffee trade (from 1714 to 1735, the island's population is multiplied sevenfold and the black/white ratio, expressing the servile structure of the coffee industry, inverts: 632 Whites for 534 Blacks in 1714, and 1716 Whites for 6573 Blacks in 1735):

"Since coffee cultivation started, the wish to make a fortune led a great number of strangers to pass through here, writes father Criais, and the employees of the Company, pushed by the same desire [it is, as we've seen, something the inhabitants reproach them], have multiplied, everything has changed and the old inhabitants have been dragged by this into old troubles (Recueil trimestriel..., t. IV, p. 185-186).

The colonial doctrine

In several texts, rules and correspondences (among others: AN. col. f3 205, chapitre 2, section 4, "des mariages, de leur conséquence, et de la Discipline qui s'y doit observer"; "Règlement de Bourbon" du 17 février 1728), the Company wishes to police weddings, doubtless to "prevent the mixture of French blood which weakens and corrupts by practicing sloth, and which worsens through everything that is called disproportionate and indecent alliances", but also to manage the distance required between its agents and the inhabitants. A letter from the 21st of September 1750 announces that the Company's employees with a Créole spouse couldn't be admitted into the upper ranks. On the 1st of March 1754, the managers specify:

"To leave no ambiguity, we repeat to you that any employee, councilor, trader or middle-man, who is presently married to a Créole woman, will be able to keep his post, but he won't be able to reach a higher level without the Company's approval; from now one no position will be granted to Créoles, and no employee will be able to marry one without the Company's approval. Furthermore, we mean by créole, any child born of mixed blood because the children born in the isles to unmixed European fathers and mothers, aren't counted as créoles, neither in the class which is excluded here (ADR. c° 152, "Les Syndics et les Directeurs de la Compagnie des Indes, au Conseil Supérieur de Bourbon", Paris, le 1er mars 1754).

This application of the term "créole" only to mixed-bloods only answers imperfectly to the colonial doctrine which must, if the Company wishes to prevent conflicts of interests, set apart the inhabitants, white and métis7 included in a same "créolity", its officers and its agents. Bouvet de Lozier argues in this way, in a letter addressed to "Messrs the representatives and managers of the India Company" dated to the 4th of November 1754:

"The Company's letter from the 1st of March says, regarding the weddings of employees, that "through the term of créoles, it only means métis girls from a mixture of black and white blood, and not girls born of whites and white women.' This rule may be enough for l'Ile de France for a time, but regarding Bourbon, it seems that the Company has until now given the term créole a wider application, and that it fears not only that these alliances would prevent the respect due to its employees, but also that they be an obstacle to its business." If it happens that some business, indeed, concerning the families "with which the employees of the pen or the sword established there are allies" "must be carried before the Council", "one could think that the councilors living on the island would be more likely to side with the inhabitant than with the Company". Indeed, "the Company forbade several times [...] to allow any inhabitant access to the Council." Thus sieur Dehaume, who 'always acted with wisdom and competence", "only has against him the fact he is married to a créole" (Archives d'Outre-Mer d'Aix-en-Provence, cotes c4 8 et C4 9). Bouvet still, in the same spirit on the 21st of January 1752: "Sir Roudic could have been a councilor if he hadn't married a créole following the permission given to him by the Company in the previous expeditions." (A.O.M. registre C3 7) . "Weddings must still be a point of interest for the Company, argues in the same way the "Mémoire on the isles of France and of Bourbon" from 1753. It must not suffer for any employee to marry créoles. This causes cooperations and alliances that will always be quite dangerous for its business" (AOM registre C3 7). In a letter from the 27th of June 1741, the Company "approves [of Héguerty, particular governor of Bourbon] that he has separated himself from his habitation, finding it improper that those in charge of its affairs, particularly in Bourbon, had some interest in living with the inhabitants." (Correspondance, t. IV, p. 32). Dependency and inequality of men are indeed constitutive of colonial feudalism.

Doubtless, the more a vassal is burdened, the less motivated he is and the system that exploits the colonists could be less implacable and more productive, but its "injustice" is structural in nature. The impression of the inhabitants of Bourbon, in the anonymous memoir of the 9th of March 1727 cited above, states that "the colony's wealth would be assured" if "one removed from the governors and authorities the power to own any concessions in the colony, because otherwise it wouldn't be necessary for there to be any other inhabitants but them, because they'll soon possess all the concessions of said island", and, excluding style, touches upon a truth. Desforges-Boucher thus was conceded land between the Ravine de l'étang du Gol and the Ravine des Cafres. Pierre Benoist-Dumas, General Manager of trade for the India Company makes for himself in one year a patrimony estimated at 885 hectares. "In 1731, writes Mas, the four strongest coffee producers on the island are Justamont and Dioré, previously governors, Dumas, governor, and Feydau-Dumegnil, member of the High Council" (Mas 1971 op. cit. p. 36). (see: "the goods of P.B. Dumas in the isle of Bourbon" in Recueil... t. VII, p. 111) Dumas plants 45.000 coffee trees in Saint-Suzanne and possesses 30.000 in Saint Paul, Dioré 40.000... In contradiction to the appraisal cited above, regarding the issues of its representatives "having some interest in living with the inhabitants", the Company granted its officers a right of privileged access for buying concessions (similarly to Canada or the islands of the West Indies, see: P. Blanc, 1958, A propos des concessions domaniales outre-mer sous l'Ancien Régime, Paris: Librairie Générale de Droit et de Jurisprudence). It must be added that at the beginning of the island's settlement, "concessions were handed out liberally and without any caution... the lack of contracts which were the cause of the greatest inconveniences came from the immensity of the lands granted to each inhabitant" (report from 1785 by Davelu, cited by Mas, op. cit. p. 163). Mas gives some examples: Jacques Auber and Gilles Dennemont who were ceded approximately 5000 hectares (including ravines and hilltops), Samson Lebeau 1.500 (id. p. 164). In 1710, the Memoir of Antoine Boucher observed: "there are inhabitants with a hundred times more lands than what they can cultivate" (this memoir is published in tome V of the Recueil Trimestriel).

Wasteful and impolitical usage of the goods that are the land and the colonists? Yet perfectly articulated in their intention, as expressed in a letter from the 10th of October 1725 from the Company's managers to the Bourbon High Council (in which the Company complains about coffee's lack of success: "It is tired of hearing you promise, for four years now, an ample coffee harvest [...] and of seeing itself at the end of this span of time in the same position as on the first day.") : "You must only have two aims in sight, and these are two capital points: the first, is to cultivate the island's interior, to which you must apply yourselves whole-heartedly; the second is to make it so the inhabitant is always in the Company's debt. Through this second point you'll easily manage the first one because the inhabitant will redouble his care and work to repay us, and will provide the produce of his land." (Correspondance, t. I, 1724-1731, p. 6-7, emphasis ours). The island's cultivation rests on the "forced labour" of indebted inhabitants, forced to reimburse the Company with the coffee they produce at a fixed price for it. "The inhabitant who lacks money to pay for his adjudication, and who'll receive a loan from us, will only be allowed to pay us back with produce from the land itself, and will thus pay in coffee" (id. p. 19). Indeed, many inhabitants are insolvent. In a letter dating from the 20th of October 1731, the Bourbon High Council analyses: "All we have the honour of telling you is that they are almost all very poor, that the richest in liquidity don't own more than 4 or 5 thousand silver écus8" (Correspondance, t. I, 1724-1731, p. 142-143). A letter from the 1st of April 1732 specifies that only "the old inhabitants, people that have had slaves for a long time, and in sufficient numbers, have profited by their habitations, the first to plant coffee trees, and consequently didn't indebt themselves with the Company, but on the contrary became its creditors... It's for these that we need yearly for money and some commodities with which to pay for their coffee and produce" (id. 1732-1736, p. 145). The same letter adds, that on the contrary, those that recently established themselves "who bought blacks for 2 or 3 hundred piastres9, and everything that was necessary to develop their habitation, which cost them far more these days than what it once cost. These people... Are in it up to their necks and owe considerable amounts" (id. 1732-1736, p. 2, emphasis ours). Indeed, without counting the "indispensable advance payments, during the first four years", one needs "no fewer than 12 Blacks" to make a habitation profitable - in 1732 over 300 habitations "were only starting" (id. p. 4). The twelve Blacks here are supposed to cost 24 trade rifles to the Company, which sells them 4000 pounds to the inhabitants. Regarding the coming coffee crisis, "6% of the islands' producers provide 47.8% of total production, and employ 1163 slaves (average of more than 58 slaves per house)" (C. Mazet, "L'Ile de Bourbon en 1735...", loc. cit. p. 33). In the first slave trade operation organised from Paris and entrusted to the Courrier de Bourbon commanded by captain Antoine Dufour, in 1717 and 1718, point °10 of the "Instructions and orders" (document A) of the Company specifies: he "will do what he can to have three Blacks, young and well-made, for two rifles, or at least three Negro women if he can't have two for each rifle, or one Black for a pistol." (Recueil trimestriel de documents et travaux inédits pour servir à l'histoire des Mascareignes françaises, 1935-1933-1934, Saint-Denis, p. 385).

A society of servitude (Mas 1989, loc. cit. p. 109)

The first Bourbonese are, as expressed in several items of Jacob de la Haye's ordinances, hired men paid in "credit and salaries".

Item 12. - "No one will go hunting..." "Six months of services without credit nor salary for the first time and in case of recidivism the death penalty" in case one can't pay a twenty écu fine.

Item 21. - "That all those who deserted and went to live in the mountain, will be excluded and deprived of any reward, salary and payment, and their property confiscated by the king."

Item 25. - "It is forbidden [for hunters] to traffic, trade, sell or carry game elsewhere than to the stores [...] on pain [...] of staying on the island for two years at their expense, without any credit or salary, and, in case of recidivism, to be hanged and strangled."

Their fate, the island being unexploited, isn't that of the hired men from the Antilles, where there are plantations and "masters" (and where "the masters [care] far less for a white hire than a black slave, and have far fewer feelings about the death of a white hire than that of a slave because they lose more from one than from the other" - intendant Robert, in 1698, cited by Debien, p. 206-207; see: Madagascar; l'"Originaire", l'"Engagé", et l'"Habitant"). The men of Fort-Dauphin, under Pronis, for their part, "thought it quite strange to fulfill in this country the functions of porters and slaves, [despite] seeing many Negroes in the house that weren't made to work" (Flavourt, Histoire..., P. 296). These hired men become, in fact, colonists and their work is often that of settling. They are given lands under the condition of cultivating them, on pain of confiscation. They bring with them an idea of property and familial transmission, an expression of the domestic unit led by the husband, the wife and their children, specific to European peasant societies. A document regarding a concession, dated to the 20th of January 1690 and signed by governor Vauboulon, sums up this ideal: "Anathase Touchard, writes Vauboulon, shows us again that in the twenty years that he's lived on this island, he has always worked with the pain of knowing that the land he cultivated wasn't his, and that based on the vagaries of those who were in charge until now, he always had to be ready to leave it, with the worry that after his death, he wouldn't be able to leave anything to his wife and his children, which would make his situation as unfortunate as that of the slaves who own nothing for themselves, and who can't acquire anything [...] He requests our justice and authority and asks of us the ownership and funds of half the habitation where he lives..." (cited by Mas, 1971, annex n°3).

"The inhabitant's burden" ...

"The Company received, note the Managers in a letter from the 24th of September 1729, a copy of the judgement that sir de Brousse, in a war council, pronounced against one Languedoc, a soldier." "This judgement, they comment, is most irregular, because the Council gives itself the right it doesn't possess to pardon a man it's supposed to condemn [and furthermore, imposes on him] the burden of becoming an inhabitant", "which, they correct, must be regarded as a pardon by any honest man" (Correspondance, t. 1, p. 93). With the coffee crisis, starting in 1736, the situation of the inhabitants degrades consequently and most find themselves incapable of reimbursing their loans. "We are burdened by immense debts. Some are to your profit, and we will never alter in any way our arrangement in this regard; but these aids came to a halt too soon and change forced us to take up new ones... We had to have recourse to private individuals who being less interested in the public good than in their own interests, made us the victims of their thirst for riches. An unfortunate necessity which has subsisted since 1735... and led us to the most awful poverty... Far from being able to discharge our debts, we would be in twenty years even worse-off than we are now" ("Supplication of the Bourbon colonists regarding the price of their coffee in December 1746", dans: Recueil trimestriel..., 1937-1938, p. 176; see also the letter of the Managers of the Company of the 30th of March 1746, Correspondance, t. 4, p. 247). At the time Bourbon is ceded back, 8/10ths of the inhabitants are indebted to the Company.

The conclusion of this development can be left to Adam Smith: "Some nations relinquished all the trade of their colonies to an exclusive company, forcing the colonists to buy from it all the European commodities they could need, and to sell to it the totality of their unneeded produce. The company's interest has thus not only been to sell the former as expensively as possible, and to buy the other as cheaply as possible, but also to only buy of this one, even at this low price, only the amount it could hope to dispose of in Europe at a very high price: its interest has been not only in degrading, in all cases, the value of the unneeded produce of the colonists, but, furthermore, in most circumstances, to prevent the increase of this quantity, and to hold it below its natural state. Of all the expedients one could devise to compress the progression of the natural growth of a new colony, the most efficient, without a doubt, is that of an exclusive company. (Adam Smith, Recherches sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations, traduction Garnier, édition de 1843, livre IV, chapitre VII, p. 185-186, our emphasis).

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this lengthy digression into the early history and economics of the island. My corpus of substack and X (twitter) posts on Réunion thus now covers most of the island’s history from its discovery to the mid 20th century, including its ecosystems, agricultural system, economy and demographics. I’ll probably give this topic a rest for the foreseeable future, but no promises because many ecological topics and species on this fascinating island are worthy of in-depth investigation.

The act by slaves, especially Malagasy, to flee their masters’ plantations and seek refuge in the mountains, living off foraging, theft and banditry. Developed in the two previous essays especially.

Originally meant the earliest European settlers of the island and their descendants. Nowadays refers generally to the mixed-race people inhabiting said island and other old French island-colonies like it.

Madagascar.

One of the first governors of the island had guaranteed a fixed price for the settlers to buy slaves, in order to cultivate the land and make the colony profitable.

Developed in a previous essay, an India piece was a piece of textile worth as much as one healthy black slave. Later the term came to designate such a person directly.

A French “Ancien régime” unit worth a little under half a metric ton.

Current term for mixed-race French citizens, especially within the context of overseas territories.

Ancien régime unit of currency.

Term designating in France coins made of silver, linked to currencies used especially around the Mediterranean at the time.

I'm gonna share this one with my readers. Good stuff.