The original coffee startup

How France turned a barely-inhabited island into a coffee juggernaut

Introduction

Over the course of the several last posts, translating French essays on the history of the French island of Réunion, we have learned about the disastrous first colonisation of its sister-island Madagascar, the lives and tribulations of the first people to settle there, their legal status as serfs of the India Company of France, and finally the international slave trade out of Africa, Arabia and India which provided the manpower necessary for the maintenance of the vast plantations the corporation wished to see grow on its lands.

Today’s text is about coffee, the first of several “cash crops” which took agriculture on the island by storm. France at the time (early 18th century) did not have sovereign possession of many lands which allowed the growing of “exotic” tropical spices and fruits, so the discovery that Réunion was able to support the coffee tree, already fast becoming a massive consumer good in Europe in those days, created a frenzy of activity to develop this crop as much as possible, bypassing the need to trade with outside powers.

Through strategic importation of manpower, slavery and coercion of the population, the Company would manage to turn a ragged, and half-forgotten island of hunter-gatherers into a plantation of tens of thousands of coffee trees, producing hundreds of thousands of pounds of beans per year.

The translated text is taken from https://www.anthropologieenligne.com/index.html and credit goes to Bernard CHAMPION.

The inhabitant's burden

"At the end of the century, writes Albert Lougnon, it wasn't quite certain who was responsible for Bourbon. The managers of the India Company evoked the successive retrocessions of Madagascar, of the 'forts and habitations that depend of it', to vehemently affirm that Mascarin didn't belong to them, to assure that they never claimed to make anything out of it and that they didn't wish to make use of it in the future, being too far from Europe and too close the Indies... There being no shelters, bad harbours, and awful currents." (The managers of the India Company at Pontchartrain. Paris, 9 février 1698, AOMN, C2 f° 11, cité par Lougnon, l'île Bourbon pendant la Régence, Desforges Boucher, les débuts du café, Paris: Larose, 1956, p. 16-17). In 1710, "only a quarter of the conceded lands were cultivated" (Memoire de la Cie à Parat, Recueil, cité par Mas, 1971, op. cit. p. 53). "The approximately 1500 people inhabiting the island in 1715, concludes Lougnon, the coffee historian, passionate about hunting and fishing, the masters as well as the slaves, seem reluctant to carry out any work and are completely lacking in initiative." "This rock being more or less useless to it, the East India Company first pretended to ignore it" (Lougnon, op. cit. p. 333-334).

On the coffee-trees of the isle of Bourbon (hist. pag. 34, Académie royale des sciences de Paris. Botanique. Année 1716).

The inhabitants of the isle of Bourbon close to that of Madagascar, having seen from a French ship coming back from Mokha in Arabia1, branches of the ordinary coffee-tree laden with leaves and fruit, immediately recognised that they had in their mountains identical trees, and went to seek branches whose comparison convinced our people. Only the coffee of the isle of Bourbon is longer, thinner, greener than that of Araby, & it is said that being roasted or burnt, it's more bitter. Mr. de Jussieu said this to Mr. Gaudron, Master of the Saint-Malo apothecary. It'd be an advantage for the Kingdom to have a colony from which it could draw this fruit which came so prodigiously into fashion. The difference between the coffee of the isle of Bourbon and that of Yemen may perhaps be advantageous to the former, when it'll be well-known, or else we will find a way to correct it.

From 1716, the History of the Royal Academy of Sciences (1716, p. 34) officially mentions the discovery of an indigenous coffee tree in Bourbon. The transportation, by the Chasseur, of about sixty coffee trees from Mokha, in 1715, that an agent by the name of Imbert managed to procure, the news, reported by governor Parat that Bourbon possesses an indigenous coffee tree, the opinion of Antoine de Jussieu that it's true coffee, the excitement around colonial undertakings, all this determines, in 1717, the setting up of a plan for the rational exploitation of the island (see: Lougnon, p. 334) ...

(The story of coffee in Réunion... by Albert Lougnon, The isle of Bourbon during the Regency, Desforges-Boucher, the beginnings of coffee, Paris: Larose, 1956)

The Company's secretary general, Louis Boyvin d'Hardancourt, is given a mission by the managers to evaluate the counters. He sojourns in Puducherry, then in Bourbon from the 20th of April to the 3rd of September 1711. During an excursion in the area of Saint-Paul, he discovers an indigenous coffee tree. "This coffee is a little larger than that of Mokha and has pointed extremities." (Memoir of M. Hardancourt, pp. 132-133) (Lougnon, op. cit., p. 61). This indigenous coffee trees was only described in 1783, by Lamarck, under the name of Coffea mauritiana. The first published mention of Bourbon's indigenous coffee is found in the History of the Royal Academy of Sciences, year 1716, 1718, p. 34, under the title of "Botanical observations" (supra).

Ponchartrain, secretary of State of the navy: to the captain of the Auguste, on the 31st of October 1714: "The managers of the India co. needing to draw from Mokha where you're headed trees which produce coffee, the King's intent is that you load there as much as you'll be able of these trees to hand them to the Governor of the isle of Bourbon who'll be sure to plant and cultivate them. Since you must pass through the Malabar coast, his Highness desires for you to take plants and shrubs which produce wild pepper and cinnamon [the latter meant to be rootstock], and that you similarly give them to this governor." (p. 69-70)

Considering the importance of "such an advantageous event" as "the new discovery of coffee made on this island", it was urgent to send someone to France, both to inform the Court as well as to provide the necessary precisions which could be needed regarding what to do in such circumstances". Governor Parat himself was deputised to do this... (11 nov. 1715).

The Chasseur "laid anchor at Saint-Paul on the 25th of September 1715 and unloaded twenty coffee trees of the sixty taken in from Mokha, the others having died out" (p. 73)

"Of the twenty coffee trees from Mokha that the Chasseur offloaded in late September 1715, eighteen didn't resist transplantation. The last two, given over to the care of the brothers Martin, living in Saint-Denis had just finished taking root. In September 1717, they were covered in flowers. One could then see, wrote Justamond, that it was another species than the indigenous one because "the wood and the leaf were different". Of the seeds that were picked in early 1718, 605 were given to 32 inhabitants of Saint-Denis, including 450 to the Martin brothers, and 78 to 23 colonists in Saint-Suzanne. Of these 603 seeds, 484 didn't germinate, and of the 199 plants that came from the rest, 82 were destroyed by animals. The lineage itself came close to disappearing." (p. 115). In the month of January 1719, the Martin brothers' coffee tree started producing, for the second time, ripe seeds. They were handed out until July. [...] 2.693 seeds were distributed to 123 inhabitants. [...] We were rewarded with 779 plants, joining the 117 survivors of last year's plantings, meaning that at the end of the year 1719 we had a total of 896 saplings. In May 1720, third harvest [...] 15.000 seeds were sown, which, in October, produced 7.000 plants" (p. 151) (A. Lougnon according to the calculations of Guet).

Eighteen to twenty months after the seed was put into the ground we have a sapling five feet tall. From then on it flowers and the fruits are ripe before the second year. The Mokha coffee tree carries both flowers and fruits so that two harvests can be made, one in March and April, the other in June and July, but the second is three quarters less productive and the seed is no larger than that which comes from Araby while the beans of the first are double the volume. The total is considerable. The original tree in three years, hasn't produced less than "fifteen pounds of coffee, even if it lost more than half". A single problem, and an important one: the berries ripen during hurricane season. It'd be interesting to make it so it happens in November or December. We will try, to manage this, to graft the Mokha coffee tree on the indigenous one." (p. 152)

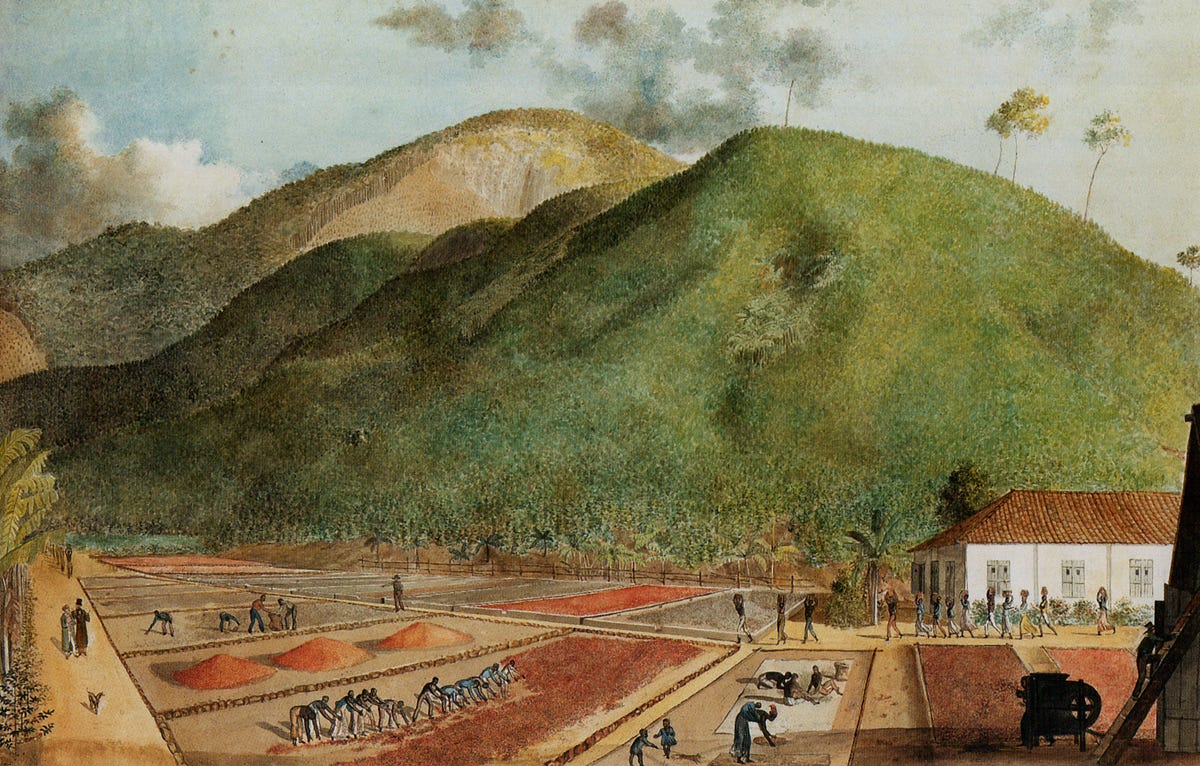

"When on a beautiful morning I arrived at the base of these fertile slopes, I thought I heard, and I indeed heard, but from quite a great distance, a choir of two parts whose perfectly accorded voices rose and fell one after the other: the songs were interrupted by prolonged sounds similar to those of a hunting horn. "How do you find this music?" asks the inhabitant that accompanied me [...] The créole, he added, who after a long trip would return to his homeland, could not, it seems to me, stay emotionless before the song of the blacks working in the mountain, this sound far away from the encive2 that thus reverberates in the rocks [...] There was a great agitation on the argamasse [note: outside courtyard] of the house; two hundred blacks were busy grinding last year's coffee; they were arrayed on both sides of the long piece of wood in which large mortars had been carved; with strong pestles that marked the rhythm of their song, they broke the tough and dry pulp that surrounds the coffee bean [...] The negro women were only there to encourage the blacks in the first moments; they soon met with the pregnant women and children occupying another part of the argamasse. As the coffee started to be ground up, blacks carried it to the winnowing mill, similar to our wheat winnowing mills, or, which was for the best, carried it to the top of quite a high scaffolding and then let it fall: the broken bark flies off like the chaff from our grain; the beans, heavier, stay beneath the scaffold; the negro women collected them to finish cleaning them, by getting rid of defective grain or those that the grinding had broken. The children helped a little with this work. The wet-nurses made vacoa3-fiber bags, in which you see our Bourbon coffee arrive in Europe. The white manager with his iron-banded staff in hand, the armed commanders of the chabouc4, walked through the work, hitting the lazy, and dispatching work to all hands." (Auguste Billiard, Voyage... 1822, p. 92-94).

"What joy to have in French lands drugs and spices such as those the Arabs and Indians only granted us in exchange for precious metals! The good Bourbonese would limit themselves, or so they claim, to trading the produce of their harvests for commodities from the métropole, and the principles of mercantilism would be safegarded." (Lougnon, op. cit., p. 79). The "good Bourbonese"? The 1713 census counts 633 free men and 533 slaves. "We received half a dozen from Maurice, four in 1707 [...] Most came from passing ships that had picked them up in Mozambique, Madagascar or in India, twenty-six from an Englishman in 1699, sixteen from two Scotsmen in June 1702 [...] about thirty from Puducherry in 1707 and a few more in 1710." In everyday terms, Lougnon concludes: "All this wasn't very much, and if one really wanted to practice the cultivation of spices, the importation of a massive workforce was to be considered" (id. p. 105). The colonists also had to be made to profit from these cash crops and the colony had to be reorganised as a consequence.

The 1717 colonisation plan

To support its two administrators, the governor and the store-keeper, the Company puts in place a major and an aide, the store-keeper being promoted to lieutenant in the government. The Company's managers delegate full administrative, judiciary and legislative powers to the governor. An inventory of titles and possessions became necessary as soon as a rational exploitation of coffee was expected. "Considering that several inhabitants had obtained from the governors lands of such an extent that they couldn't cultivate all of them, writes Lougnon; that some, alleging the depletion of their money, constantly requested new lands while refusing that the abandonned ones be ceded to third parties, the managers [...] obtained from Louis XIV, on the 27th of February 1713, an ordinance according to which all the titles of concessions for lands in Bourbon would be presented to the provincial Council to "have their extent be known", after which new contracts would be delivered for free "for sums that will be agreed upon". This ordinance hadn't been carried out. The managers agreed to do so." (id. p. 86-87).

It's also an opportunity for the Company, "after reminding of the obligation to cultivate within a time-span of three years, on pain of the land being rejoined to that of the Company", to introduce new clauses. "Each year, in the month of January, the tenant would have to pay the sum of five pennies per arpent, in silver or in kind, in recognition of lordship under the cens et rentes5, and to provide to the store one chicken and one capon6 for rent. Furthermore, the inhabitants would deliver part of the coffee and the pepper they'll collect both on unceded lands and their own properties, half or the third in the first case, a fifth in the second case. At last at every change in ownership the rights of lods et ventes7 will be collected for one penny eight deniers per numerical pound, or 12% of the price. In exchange for this the inhabitants won't have to pay the tithe to the clergy." (id. p. 87: 10 nov. 1717 "Instructions et ordres de la Cie des Indes pour Messieurs Beau voilliers (sic) de Courchant, gouverneur, Boucher lientenant [...]"). Boucher, despite the opposition of the naval Council (on account of his birth and his reputation for unseriousness), is made the governor's second. He was to "motivate, train and instruct the inhabitants in the cultivation of all the fruits growing there that could be cultivated... conduct a search for mines, metals and minerals... ensure the restriction of [the lands] that were previously ceded without thought and out of proportion based on the forceful representations of those that asked for them... take care of [their] cens and yearly rents... manage as a leader all the trade of said isle of Bourbon" (id. p. 90).

This programme puts in place additional constraints for the colonists. First, the addition in contracts of an obligation to cultivate coffee. The concept is put into practice in a concession made to Jacques Auber, on the 4th of September 1719, who "promises and makes it his obligation to cultivate and bring valure to the land that will be ceded to him and to mainly busy himself with the cultivation of coffee" (Mas 1971, op. cit., p. 57). On the 4th of December 1715, the provincial Council had decided (before the Company chose Mokha) that "each working man, white as well as black, from the age of fifteen up to sixty" would be made to cultivate a hundred trees that he'd take from the woods and replant with five feet of spacing between each of them, as well as picking a pound of this wild coffee to be handed over, dry and clean, to the island's commander "at the Notre-Dame of March8 at the latest" (ADR, C° 1, f° 32). "The vagrants and layabouts, with no distinction, will know that if they don't start working they will be employed for public works as the governors will judge appropriate" stipulates the ordinance of the 21st of November 1718). The inhabitants who "in 1715 barely paid the king any tax" must now take part in expenses. The order was given in 1717, as noted, to revise the contracts on land grants, to limit the extent of the properties, to make them pay a cens in recognition of lordship and a payment in kind, and to subject them to the right of lods et de ventes in case of change of ownership, to force the inhabitants to give for free to the Company one-fifth of the coffee they'd collect on their own properties. In 1724, lordly corvée labour was instituted for the sole profit of the ruler and not the collectivity (Lougnon, op. cit. p. 338).

These constraints prove to be dubiously effective. Desforges-Boucher had an ordinance made in 1724 concerning the cancellation of concessions which didn't carry "coffee trees originating from Mokha". The "fulminations" of Desforges-Boucher against the inhabitants were often reported, notes Lougnon. For seven years now he hasn't stopped encouraging them to cultivate Mokha coffee "by means which would have flattered the ambitions of people more zealous in carrying out their sovereign's orders and more sensitive to the quick and visible fortune that such a crop could provide them, than are most of the inhabitants of this island." He observed that the majority hadn't delivered "a single pound of coffee" to the Company's stores. He described such a conduct as "disobedient mutiny" in an island that "none other of its size in the world could rival in riches if all the inhabitants imitated the few, and applied themselves to help it blossom through the cultivation of true coffee originating from Mokha". Consequently, the high Council declared "from now on all concessions will be foreclosed... starting in the coming month of May... if there aren't at least 200 coffee trees bearing fruit or ready to bear fruit the following year, per black worker on the premises" (id. p. 272). The Company's managers grow impatient and send Pierre Lenoir on a mission to the Mascareignes. Pierre Lenoir, who'll become governor of Puducherry, arrives with instructions which are "a recapitulation of the orders given since 1717" (id. p. 310). He was first and foremost to carry out a census of planted coffee trees, which was impossible considering the "considerable" amount (id. p. 329). Indeed, "the coffee tree is definitely developing [...] the coffee tree introduced from Araby is coming into its own marvelously. It was not possible, in 1726, to make a census of them." After a laborious start, "from 1727 onward the exports exceed 100.000 pounds" (id. p. 340). Lenoir concludes his mission by denying Desforges-Boucher his role in promoting the coffee crop. "It isn't the solicitations that Mr. Desforges claimed to have made to the inhabitants which multiplied the coffee crop, but the simple motive of profit which motivated them." (id. p. 331).

The period of coffee, with the carrying out of the 1717 colonisation plan, reveals the nature of the relations of the "lords of the Company" and their colonists and the reality of an exclusive regime. The obligation to cultivate with a double customs tax based on the monopoly of trade confines the colonists in a situation of extreme dependency. The means of production and the results of the work, the land, the seeds, the tools, the workforce, the crops and the commodities, all is in the hands of the Company. And it sets the prices. Money is in theory useless in this economic configuration where the colonists acquire commodities based on the amount of crops they bring to the "king's store". In truth, the questions of currency and the lack of commodities are a reoccuring ones in this colony which is "exploited" and "abandoned"...

Conclusion

This was our second-to-last foray into the early history of Réunion. Terrible deforestation would ensue from the development of the coffee cash-crop on the island, only the first of several such crazes which would eventually see the near-extinction of the dry scrub forests of the western coast of the island, and severely reduce the extent of the lowland rainforest. Eventually, changes in market demand, disease, and hurricane troubles would doom this crop which would be cast aside in favour of an even more profitable one: sugar cane.

The last post in this series will explore how difficult life was in this corporate-sponsored colonial scheme, not only for the black slaves but also the white colonists from France. From the greed of local administrators, absolute rulers of their fiefdom thousands of miles away from the central office, to the invasive laws and regulations of the corporation itself (seeking to mould local society into the most productive configuration possible), life was stifling and harsh and freedom was in short supply.

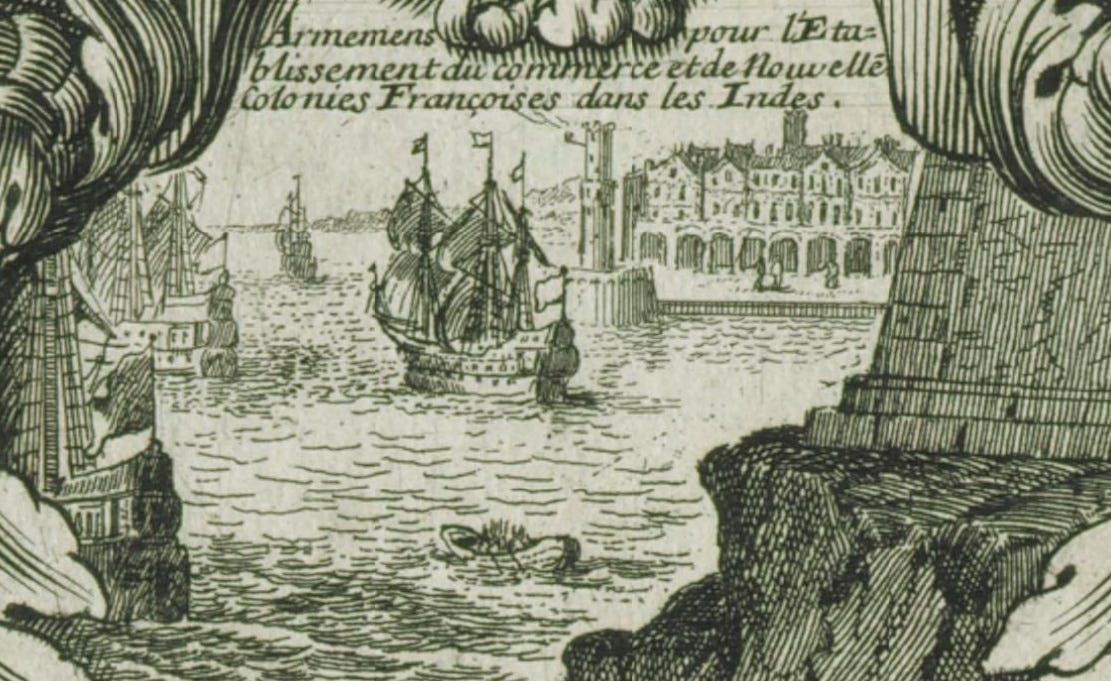

The main port of the capital of Yemen

No clue what this is

Vacoa, or Pandanus utilis, is a small tree indigenous to Réunion whose leaves were used for fiber, or making roofs for the wooden huts of the early inhabitants. The edible but unpalatable fruits were mostly reserved for periods of scarcity, or as a side dish in a more savoury meal.

A type of whip made of braided aloe plant fiber, traditionally used on Réunion for slave-driving

Yearly rent paid on property to a lord in the French feudal and Ancien Régime system

A neutered rooster, the process leading to it becoming fatter and with a more tender flesh than regular roosters

Another feudal tax from France, with the feudal lord who’s ultimately the owner of a property being awarded a percentage of the proceedings on every transaction involving said property (one tenant selling the land to another, or a tenant passing it on to his son)

25th of March