We meet again, for the last post in the ongoing Reunion island series. We started over 9 months ago with the lowest level of the island, the sandy coast, and end now with some of the highest locations there. The first part of this post, giving context on rainforest formation and the lowlands of Reunion, can be found here.

As discussed in the previous post, Reunion’s rainforests are almost all present on the island’s windward coast, and divided between the lowland rainforest, below an altitude of approximately 1000 metres, and the cloud forest at higher altitudes. Above the cloud forest we transition to an alpine environment, a different and much more rugged biome of shrubs and stunted trees which I’ve talked about previously on twitter.

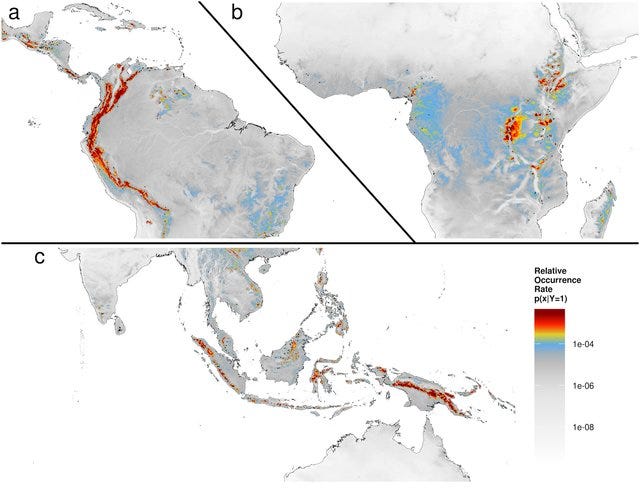

This biome is unique to Reunion in the archipelago, because the other two islands, Mauritius and Rodrigues, lack the necessary mountainous peaks. As such, this biome, much like the alpine moors, has a very high degree of species endemism. Cloud-forests are some of the most biodiverse but also most threatened habitats on the planet, covering a very small part of the Earth’s surface despite harbouring a significant proportion of the planet’s diversity in terms of animals and plants, especially ferns. The journal Nature suggests that, despite only covering 0.4% of the Earth’s surface, cloud forests possess 15% of the entire diversity of species for the following groups combined: birds, mammals, amphibians, tree ferns. Despite this, 2.4% of all cloud forests were destroyed between 2001 and 20211.

Epiphytes of the cloud forest

The cloud forest is an environment with even higher humidity saturation than the already very humid rainforest, owing its name to the fact that rain clouds constantly float over the vicinity at the level of the canopy. This allows many water-limited species such as ferns or mosses to thrive in this environment, usually leading to a high rate of epiphytism. Epiphytism is a behaviour wherein an organism grows entirely on another plant. Whether in temperate or tropical environments, lichens, mosses, liverworts and sometimes fungi are the most common epiphytic groups. In the cloud forest, ferns and flowering plants, most notably orchids, commonly join them.

Here are a few of the most easily recogniseable epiphytic species of Reunion:

the genus Usnea, cosmopolitan lichens found in all mid-to-high altitude rainforests. They’re extremely sensitive to air pollution and have impressive anti-bacterial and anti-fungal properties, being used in folk medicine.

Lepisorus excavatus is a small fern of the Polypodiaceae family that’s found throughout tropical sub-Saharan Africa. It grows on the topmost branches of trees, poking at an angle and exposing the large masses of spores on the underside of its single undivided frond.

Bulbophyllum nutans is an orchid that prefers to grow on tree trunks, sometimes vertically. It spreads vegetatively in a straight line by cloning itself through the root and is easily recogniseable thanks to its thick green “pseudo-bulb”. When flowering, it forms a dense spike of tiny, relatively colourless flowers, unlike temperate orchids which tend to produce very eye-catching flowers.

Hymenophyllum is a genus of plants known as “filmy ferns”. Their fronds are only one cell thick and lack stomata, leading to them requiring a near-constant supply of water to avoid desiccation. This simplistic body plan also ensures they stay small and relatively inconspicuous. The fronds are so thin as to be semi-transparent.

Pictures of epiphytes common in Reunion’s cloud forests. Top: flowering of B. nutans. Middle-Left: U. barbata. Middle-right: L. excavatus. Bottom: a species of Hymenophyllum. Respectively by: J-P Basuyaux, S. Sharnoff, R. Houlet and M. Fiz.

This biome, even though it’s already a sub-type of rainforest, is a complex and stratified environment which can be further sub-divided into four types. However, it should be noted that in most cases, species from different types with overlapping ecological requirements can cohabitate, but it’s usually clear which type of vegetal assemblage dominates the area.

The lower cloud forest

The lowest altitude and mildest cloud forest assemblage is known as the “colour wood” forest. It’s so-called because of the abundant presences of trees of the Dombeya genus, called “mahots” in créole, which have colourful flowers. These are members of the family Malvaceae, which in temperate climes are herbaceous plants known for their large, generally fuchsia pink, flowers, possessing many stamens (plant male organ) fused together as a column around the female organ, the pistil. Here however they have evolved into trees, the largest of which are 15 metres tall, while the other species of mahot grow to less than 10 metres. They are recogniseable not only by the slight variations in leaf shape and colouration but also their spectacular inflorescences, forming spheres of dozens of pink flowers. The largest species is “white mahot”, D. pilosa whose large heart-shaped leaves are covered in a thick, slightly sticky layer of hairs. Its cousin D. reclinata is the easiest to recognise as the hairs covering the three-pointed leaves are light-brown, giving them a slightly sickly look from afar. The two remaining main species are D. elegans, almost devoid of hair, the smallest of the mahots (the leaves often point strongly downwards, making the entire plant look wilted), and D. ficulnea, whose leaves are also covered in light-brown hairs but are pentagonal rather than three-pointed. In all cases, their large colourful flowers are visited by nectarivorous birds (such as the altitude specialist Zosterops olivaceus, which I already talked about).

Another unavoidable and oh-so-aesthetic aspect of this level of the rainforest is the presence of numerous tree ferns, a type of vegetation some associate with the cenozoic epoch, but which survived to this day in the tropics with around 700 species. The main species of Reunion are all in the genus Alsophila, and called “fanjan” in créole. They all grow to be approximately 10 metres tall and are differentiated by the level of division of their fronds and the pilosity of the rachis (tough structure that supports the photosynthetic parts of the frond). As such, A. borbonica is the most easily recogniseable species with 2 levels of division to its fronds, whereas both A. celsa and A. glaucifolia have 3. These latter two species are then distinguished by the fact that A. celsa’s rachis is hairless and dark green, while the last species has a thick light-brown pilosity there.

There is unfortunately another common species, the invasive Australian tree-fern Sphaeropteris cooperi which was cultivated as an ornamental and now occupies all the island’s rainforest ecosystems. It also has 3 levels of frond divisions, but its rachis bears long white-ish hairs that easily demarcate it from the other species.

The high-altitude cloud forest

The next level of cloud forest, higher up, is called the “tamarinaie” because it is dominated nearly exclusively by the species Acacia heterophylla, dubbed “tamarin” in créole. This tree has a thick trunk but a very superficial and under-developed root system. As a consequence it falls easily, but is quickly able to take root again from the trunk and start growing upwards again in a twisted shape. It has the particularity, as its name indicates, of simultaneously having two “shapes” of leaves. The Acacia genus is part of the family Fabaceae (most well-known in temperate climes for containing peas and clovers). These originally have composite leaves composed of separate folioles, and this species is no exception with up to 10 pairs of small round folioles per leaf. However once the leaves reach a certain age, the folioles fall off, leaving only a long and thickened petiole, which grows to become similar to a single elongated leaf. This unusual photosynthetic organ is called a phyllode. While this species’ natural environment is as an altitude pioneer which occupies clearings, clear-cuttings and grows well after fires, artificial monospecific stands of the tree are conserved and used in sylviculture, as the plant’s wood is of a high quality and used in woodworking.

Alongside the tamarins, Reunion’s only endemic bamboo can also be found spreading its leaves in the high altitude forests. This impressive and unmistakable plant was once heavily collected in the wild for use in crafting (fishing rods, basket weaving, and roof thatching on traditional créole “case” houses), but today it grows freely. Measuring up to 10 metres tall, with internodes projecting many small leaves at regular ~50cm intervals, the plant often bends over into an arched shape as time goes on.

The highest cloud forest levels

There are two remaining stages which are considered to be part of the cloud forest: the first is the “avoune”, which is a high altitude forest of Erica reunionensis. I’ve already treated this species in my twitter thread on the volcanic moors. It’s a highly drought resistant species that colonises alpine environments and the proximity of the Piton de la Fournaise volcano, but can be found as isolated individuals in the lower levels of the cloud forest. The impenetrable “avoune” environment is made up of a tangle of E. reunionensis (properly speaking more a large shrub more than a tree) and possesses a thick black litter on the ground. Organic matter decomposes very slowly there as the adverse conditions inhibit bacterial and fungal activity (high altitude climatic variations and UV radiation, dampness, and acidic soil pH). Consequently, this environment is relatively poor in biodiversity.

The final and most specialised stage of cloud forest is the mountain Pandanus stand. It occurs in altitude plateau areas with over 5000mm of precipitation per year (nearly twice as much as the wettest location in the UK). This perpetually waterlogged soil is the preferred habitat of Pandanus montanus, which is only found in those small areas, but the tree ferns discussed previously can also be found here, as well as a particular species of “palmiste” (see part 1) which only exists in altitude: Acanthophoenix crinita (previously, A. rubra). Like other palmistes, its edible heart is a highly sought-after delicacy, leading to intensive poaching.

Birds of the cloud forest

Islands, especially those far from the nearest continental landmass, are generally poor in vertebrate fauna. The exceptions to this situation are mainly flying animals, such as birds and bats. The previous post already elaborated on the most iconic rainforest bat species of Reunion, and as promised we’ll now look at the birds that inhabit its misty mountaintop forests.

Tersiphone bourbonnensis, the Reunion paradise flycatcher (“zoizo la vierge” in créole) is a small (15cm) brightly coloured species which has a stable population of about 50.000 individuals on the island, thanks to its generalist ability to subsist in most forest types and lack of value to humans. It breeds for life and will always remain in close proximity to its partner. However, it’s extremely territorial and aggressive against other conspecifics. Its nest is a small bowl made of lichens and mosses. This insectivorous bird hunts by perching on vegetation, quickly taking off to intercept prey flying overhead. Like many insular birds, it lacks any fear of humans, occasionally walking on the ground next to hikers or even perching within easy reach.

Hypsipetes borbonicus, the Reunion bulbul (“merle péï”), can live in higher altitude forests, being found up to 2000m. With its uniform black coloration and orange beak, it bears a strong resemblance to the European blackbird (Turdus merula) although it’s from a different family (Pycnonotidae as opposed to Turdidae). This mainly frugivorous species used to be extremely common on the island, according to folklore and old stories, but it was intensively hunted for its meat and for ownership as a pet until 1988. Today its population is about 40.000 individuals. It’s more gregarious but also more fearful than T. bourbonnensis, often contenting itself with staring at passersby from a high branch, out of reach. Its call is strangely reminiscent of a cat meowing and screaming and resonates far through the jungle, which can lead to some confusion for the uninitiated.

Lalage newtoni (the Reunion cuckoo-shrike, or “tuit-tuit” in créole) is the most emblematic bird of Reunion’s rainforests. This critically endangered species only occupies an area of a few tens of square kilometres inside the tamarin forest at the top of the Roche Ecrite national park, in the North-West of the island. As a matter of fact, the national park was founded specifically to conserve this bird and its remaining habitat. In 2004 only 11 breeding couples remained on the island. Even in the earliest days of the island’s occupation, they were only known from the highest impenetrable cloud forests of the island’s summits, although they were still described as quite numerous in their favoured habitat in 1865, they had become very scarce already in 1948. The main reasons for their disappearance are believed to be predation by invasive rats and cats, which occupy the entirety of the island, habitat destruction, and possibly the mass destruction of the “palmiste” trees, which were the favoured food of certain species of wood-eating beetles which were one of the cuckoo-shrike’s staples. They’re also susceptible to harm during hurricane season.

Since 2004, a campaign of mass rat extermination in the Roche Ecrite area via traps and poisoned bait (as well as population control of stray cats via catching and sterilisation) has led to a stabilisation of the population, which now counts (depending on sources) between 40 and 80 couples. This solitary, shy bird has a powerful song which is only heard during the beginning of the breeding season in August. Besides beetles, it also eats caterpillars and has been known to eat fruits on occasion. It’s currently unknown why the species only limits itself to the Roche Ecrite national park, when other suitable cloud forest biomes are elsewhere on the island. It’s possible that it’s simply an extremely sedentary species.

Invasive threats

We’ve already gone over some of the invasive species present in the lower levels of the rainforest in the previous post, but the cloud forest also faces its own particular threats. Because of Reunion’s status as a major holiday destination and the development of eco-tourism, many travelers hike through the forest trails of this rare and spectacular ecosystem. Consequently, the trails edges, which are regularly cleared, become disturbed habitats where invasive species are able to implant and multiply with ease without competition from native species. These invasive species are transported to the island, and then spread from sensitive habitat to sensitive habitat, by tiny seeds caught in the dirt on the soles of hiking shoes. It’s estimated that about 12 grams of dirt, which may contain seeds, are transported between sites on the soles of each hiker, for over 200.000 tourists on the island in 2022 alone.

The most widespread invasive species found on the hiking trails of the cloud forest are the following (in no particular order):

Persicaria capitata is a diminutive member of the buckwheat family Polygonaceae. This small Asian species is invasive on some subtropical islands (besides the Mascareignes archipelago it is also present on the Azores for example). Along trails, it forms a low, dense mat of vegetation which chokes out any other small plant trying to grow. Its numerous, small seeds are easily spread.

Solanum mauritianum, despite its name, doesn’t originate from Mauritius but South America. This hardy tree, which can grow to 5m tall, is a member of the tomato family Solanaceae. It was originally introduced in the archipelago to be used by farmers as root-stock combined with tomatoes, creating a high-productivity and disease-resistant crop. This toxic and extremely vigorous plant has since feralised and occupied nearly all the island’s ecosystems. It is also a noxious weed in most subtropical and tropical islands in the world.

Begonia cucullata (called “coeur de Jésus” in créole) is ranked high on the list of invasives on the island. This South American species, cultivated for ornamentation, has a very high seed production per flower, allowing it to spread abundantly. It is able to dominate not only disturbed habitats like trail-sides, but also the pristine understory of natural forests.

To finish off, Boehmeria penduliflora (native to temperate and subtropical Asia) was introduced to the island in 1970 as a source of fiber for local industry. This species quickly became adept at colonising disturbed habitats, especially recent lava flows and the vicinity of the Piton de la Fournaise volcano, although it’s also found a home along roads and hiking trails. It’s so good at this that it can disturb or even prevent the natural ecological succession of Reunion forests, and it produces numerous seeds small enough to be dispersed by wind or by passing animals and hikers.

Conclusion

While I could easily write 4 or 5 more posts detailing all the species I saw during my short stay on the island, I think everything I’ve written so far should be enough to give you an overview of current ecological conditions on Reunion. The aim of this post was to demonstrate that even the smallest speck of an ecosystem on the world map, covering a few hundred square kilometres on a single island, harbours thousands of species, each with their stories and woes of cohabitation with humans and the species they introduced. Any area of the world could be worthy of such an in-depth analysis, and learning the ecology of the areas you live in, or visit even briefly, can be as instructive as any history book.

To say goodbye to this series I’ve been working on for the better part of a year first on twitter then here, I propose one last créole song, and I say créole, instead of sega maloya, because it was written by a French-Guadeloupean singer, but it is well appreciated on Reunion, playing frequently on the radio, and always makes me wistful for its beaches and mountains. See you soon for posts on other topics!

Karger, Kessler, Lehnert, Jetz, 2021. Limited protection and ongoing loss of tropical cloud forest biodiversity and ecosystems worldwide. Nature Ecology & Evolution, volume 5, pages 854–862.

La Flore et la Faune Originelles des Mascareignes, by Matthieu Saliman-Hitillambeau (éditions Orphie, 2020)

La Réunion: Faune et Flore - Le Guide Naturaliste, by Stéphane Bernard, Stéphanie Dalleau-Coudert, Maëla Winckler, Roland Benard (Austral éditions, 2016)

mi-aime-a-ou.com (an excellent resource maintained by passionate naturalists and historians from the area)