Pigeonholed

From a symbol of love to a winged rat, the journey of the pigeon.

Commensalism (a relationship that differs from symbiosis in that one of the partners derives no clear benefits from the situation) seems to be a common mode of association between birds and humans. For example, I’ve spoken before of the humble house sparrow (Passer domesticus), which started life as an opportunistic scavenger of human-grown cereals at the dawn of agriculture, now unable to live independently from humans in much of its range. But there is another avian species which finds itself in a similar situation, unable to live without human help, yet not quite clearly a part of our society anymore. This deep dive will take us along the old and winding story of friendship and obsolescence between the human and the rock dove, more commonly known as the pigeon (Columba livia).

Bird’s eye view

“Rock dove” is the name given to the wild ancestor of the domesticated and feral pigeon breeds (differentiated in the literature by being called C. livia and C. livia forma domestica). This whole group of birds belongs to the family Columbidae, a quite successful clade with about 300 extant species whose combined area of distribution covers most of the planet except for the poles. It has the dubious distinction of having extinct species as some of its most well-known representatives, these being the dodo (Raphus cucullatus) and the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). However, outside of the dodo, the morphology of pigeons is quite well conserved, despite spectacular departures from the muted colour palette of Europe’s native members of the group.

Like many groups of animals, Columbidae display the greatest species diversity in the tropics, especially South-East Asia1, and they are also adept at colonising island environments, with unique species occurring in numerous islands of the Pacific and Indian oceans. This is one of the main reasons for the disproportionate number of recently extinct species within this clade, as a significant part of wildlife extinctions within recorded history were the result of island colonisation by humans and the host of animals and plants that accompany them.

The morphological characteristics of Columbidae include short blunt beaks (topped by a fleshy growth known as a cere) on small round heads, short legs, and very wide and powerful wings, connected to a disproportionately large keel (the central bone of the chest) that supports massive flight muscles, which can make up a third of the animal’s weight. This explains their very energetic flight patterns and ability for long-distance travel. They also have the peculiarity of being able to suck up liquids, unlike other birds that have to throw their head backwards to swallow the water from their beak. However, the most surprising trait of the pigeon family must doubtless be the ability of brooding parents to produce a form of “milk” from their crop (muscular pouch in the neck) under the influence of the hormone prolactin. This nutritive, cheese-like substance is formed of the top layer of mucous cells in the crop wall, which are scraped off to feed their young.2

Diet-wise, most pigeons are either granivores which mainly forage on the ground, or frugivores that rarely leave the safety of the forest canopy. The granivores have specialised crops which contain particles of ingested grit in order to abrade and eventually grind seeds beneath their tough outer shells, a feature lacking in frugivores. Opportunistically, they may feed on arthropods, small vertebrates, or certain types of plant matter. The clade contains both solitary species, and some which are (or were) notoriously gregarious.3

Meet the pigeon, pre-domestication

The wild rock dove is a palearctic species that dwells in open areas possessing cliff-faces and other steep terrain features that allow for safe nesting. It could be found all around the Mediterranean basin, in the Middle East and even as far as Central Asia and India. A granivorous and gregarious species which browses the ground extensively to feed, the rock dove is monogamous and mates for life. For reference, the terms “dove” and “pigeon” have no taxonomic basis, and are applied in an inconsistent manner across the clade, with somewhat of a tendency towards naming smaller species “doves” and larger ones “pigeons”. It should be noted that, depending on who you ask, this paragraph should either be in the past or present tense, as widespread reproduction between wild type and domesticated pigeons has produced the feral pigeon, which is now almost the sole representative of the species in the wild, with a few exceptions of isolated colonies in extremely remote areas.

The archaeological record of humanity’s first contact with rock doves, and the nature of their interactions, is quite patchy to say the least. This is partly due to innate issues with bird archaeology, their small hollow bones rarely turning up during digs unless using specialised techniques to look for them, which are not regularly employed. A compounding issue is the impossibility of differentiating intermediate forms between wild rock doves and the early domesticated pigeons. As such, a significant part of the current sources on the process are actually written (or artistic), rather than physical remains.

Nonetheless, some remains are present. For example, digs in previously Neanderthal-occupied caves in Gibraltar found layers of over a thousand pigeon bones dated up to 67.000 years ago, some of them bearing traces of burning, cutting and teeth-marks. The rock dove would indeed have been a prime source of food at the time, despite its relatively small size, thanks to the oversized flight muscles in its chest, which would have provided a goodly morsel of meat compared to most other European birds of the time. It’s uncertain how they were caught, although several theories were proposed, including climbing rocky cliffs to directly reach the nests, or using snares and nets made of grass and other perishable materials which didn’t survive to the present day. Whatever the case, this discovery was considered a major rebuke of the previous theory that Neanderthals were too dull to hunt such swift and evasive prey.4

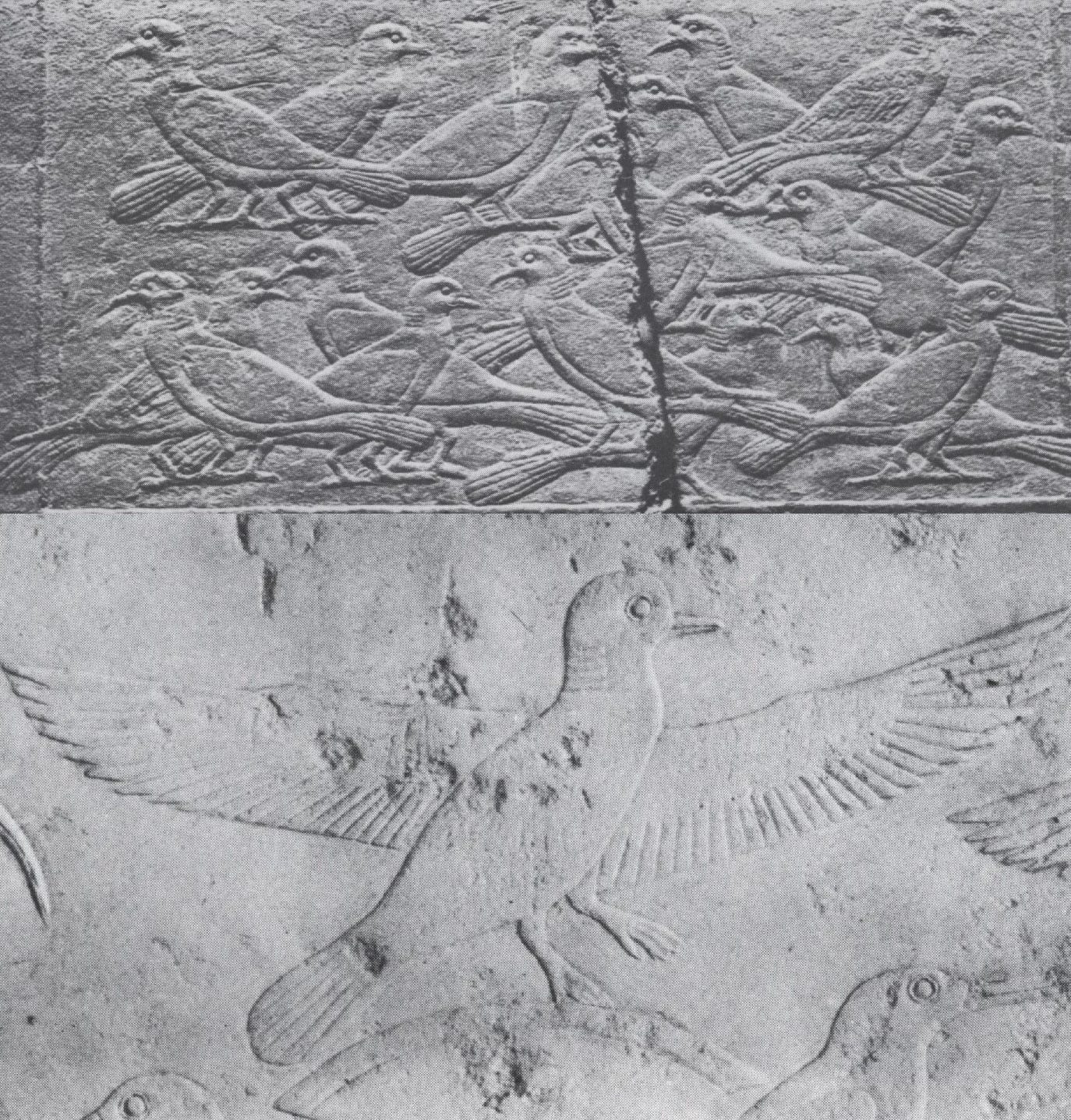

Later on, around 10,000BC, these birds were still a notable food source for hunter-gatherers, Homo sapiens this time, as attested by further finds of bones in caves located in Israel. There are numerous indications that the ancient Egyptians held the animal in some regard, with stunningly accurate bas-reliefs beginning to appear in the archaeological record starting in 2700BC.5 Many more allusions follow over the years, most notably by the Greeks, as Homer mentions in his catalogue of ships Thisbai, a port city brimming with pigeons (an observation later repeated by Strabo) and Aristotle, in his History of Animals, displays in-depth awareness of the life cycle and reproductive capabilities of the rock pigeon, comparing it to the wood pigeon and the dove before rating it as one of the most prolific breeding birds.6

Being pigeonholed

The current theory of the species’ domestication is quite similar to that of the sparrow. As soon as agriculture became an established mode of living in the Middle-East and Levant, the birds were attracted to human fields and settlements. They then quickly realised that the mud and stone dwellings found in the area were suitable replacements for the cliff-faces they used in the wild to nest away from predators. However, while the sparrow is a diminutive bird of no obvious practical use to humans, pigeons are fairly large, meaty, fast breeders (being able to nest most of the year, and lay new eggs extremely fast in case of brood failure) and produce phosphorus-rich guano which can be used as fertiliser.

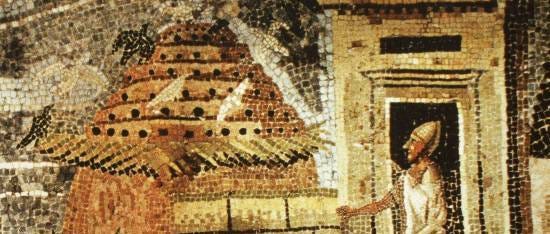

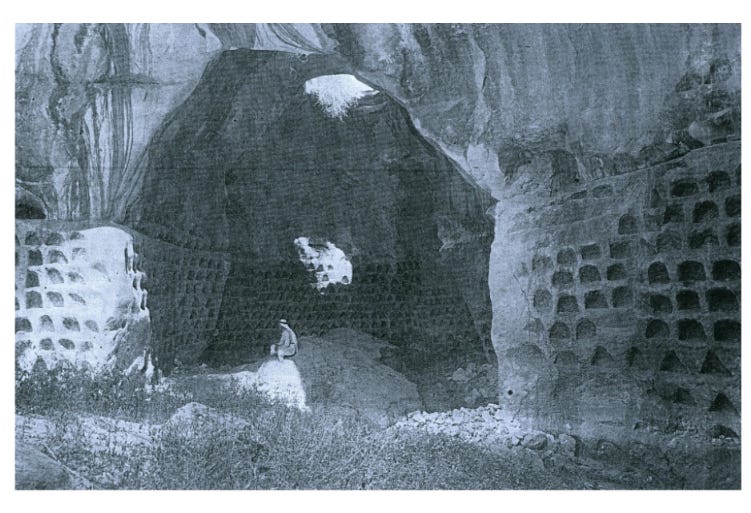

Their appreciation for small niches within buildings allowed them to easily be lured within purpose-built structures called dovecotes, or pigeon towers, initially made of mud and the oldest dated to the 8th century B.C. in Jordan7, but also elsewhere in the Levant and North Africa. This would have been a most profitable arrangement: the birds would have mostly foraged their own food throughout the year, occasionally fed agricultural scraps and a little seed, returning every evening to their nest cavity and regularly brooding. They could then have been a prime source of food, easily snatched from their nest in a moment of inattention, but also a free and local source of industrial quantities of guano fertiliser. Indeed, one paper calculates that up to 12 tonnes of guano would have been produced per year in a dovecote containing 1000 nests, enough to fertilise 1500 fruit trees in addition to a home garden8. In the areas with soft limestone hills, the bases were excavated, possibly originally as rock quarries, with the insides being turned into subterranean dovecotes. One complex in Palestine held about sixty dovecotes, with a combined 50-60,000 nesting hollows.[7]

This proximity and usefulness to humans also gave them symbolic power. The vast semi-domesticated colonies of Egypt were sometimes tapped to offer vast sacrifices of tens of thousands of birds during religious ceremonies9. Furthermore, pigeons are incredibly prolific birds. They have one of the largest reproductive periods of any Palearctic bird, and reproduce frequently within it, while staying monogamous. This led to the birds being revered in the Middle-East and North Africa region as a symbol of fertility (such as in Mesopotamia 6500 years ago), an association which continued far into modern times via the association of the dove with love10. The Assyrians also considered them sacred, while the Greeks represented doves as attributes of Aphrodite, which would be carried over by the Romans with the goddess Venus [5]. Let us not, of course, forget the preeminent place that doves and pigeons hold in the Bible: the only birds able to be offered in sacrifice to God, two young pigeons being a suitable replacement for a sacrifice of a lamb also, and the symbol of the Holy Spirit, as well as a harbinger of peace.11 12

Skybound Message Service

Their unerring ability to find their way home was made use of early on, as researchers suppose that depictions of flocks of pigeons being released from cages in Egypt (1350 BC) could depict the earliest use of messenger pigeons. They would remain a staple of fast communication, especially in a military context, until the 19th century 13 and even in the modern day!14

These abilities have been used by the likes of Julius Cesar, who sent messages back to Rome announcing his victories in the Gaulish campaigns 15 or Genghis Khan, who had pigeon relay towers installed all over his continent-spanning empire, one of the several ways he had of quickly delivering and receiving news. By the early medieval period, pigeon-rearing became an activity reserved for the elite16.

The downfall

As time progressed, the rearing of pigeons went from being a subsistence activity for peasants to a refined pastime of the aristocracy. In the United Kingdom, their ornamental and recreational role was already becoming apparent in the 16th century, and became undeniable in the 18th.17 In medieval Spain, a relatively un-codified but nonetheless enforced principle of law known as the Derechor de Palomar restricted the operation of dovecotes to feudal lords and other large landowners as well as monasteries and other ecclesiastical orders18. Charles Darwin, born of a wealthy family, was himself a dedicated pigeon fancier, a hobby which he later used to help determine the processes of selective breeding and natural selection and inspired in part his theory of evolution.19

Their main use from there on out, besides as a less frequent source of hunted food, would be delivering messages, and here history mainly remembers their role in wars. Pigeons famously ran the Prussian blockade around Paris in the Franco-German war (1870), braving bullets and trained interceptor falcons (with a return rate of about 17%). Pigeons also announced Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and were even used in some instances during conflicts in far-flung colonial theatres. Their last great moment of glory would be world war 1, where they were used by the thousands, sparing the lives of many runners by flying over the shell-wracked landscapes to bring information to HQs and forward positions in the trenches. The lightning pace of combat in world war 2 made them less effective means of communication, as most positions rarely stayed fixed for long enough to make training them worthwhile.20

All the roles of the pigeon were gradually replaced: better sources of guano, then more effective materials altogether, were found for crafting gunpowder, advances in agriculture made it less necessary to keep them as a subsistence food source, and modern chemical engineering replaced the need for guano fertiliser. With the advent of wireless messaging in the mid 20th century, the faithful pigeon would unfortunately become an obsolete tool, antiquated and forgotten.

Conclusion

Despite its tremendous fall from grace, the pigeon still enjoys a few perks from its time as a companion of humans: it’s one of the most widespread birds in the world, and is able to subsist wherever humans are present by breeding around our infrastructure and feeding on our scraps. In a way this relationship is a return to the status quo ante of the very earliest days of agriculture. Their strong breeding instinct allows them to maintain their population despite low survival rates due to the hazards of living in modern cities, and the cultivation of grains as a food staple provides them with ample sustenance in most areas of the world. One would imagine that if they could speak, they’d tell us their only regret is that they’re no longer seen as a symbol of love.

Jade Bruxaux. Phylogeny and evolution of pigeons and doves (Columbidae) at different space and time scales. Populations and Evolution [q-bio.PE]. INSA de Toulouse, 2018. English. NNT :2018ISAT0014.

Zoltan S. Gyimesi, Chapter 20 - Columbiformes, Editor(s): R. Eric Miller, Murray E. Fowler, Fowler's Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, Volume 8, W.B. Saunders, 2015, Pages 164-171, ISBN 9781455773978, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4557-7397-8.00020-7.

https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Columbidae/

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn26016-cunning-neanderthals-hunted-and-ate-wild-pigeons/

Jerolmack, 2007. https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.3.1.06

Kakish. 2012. Evidence for dove breeding in the iron age: a newly discovered dovecote at ‘Ain Al-Baida/’Amman. https://platform.almanhal.com/Files/2/34940

Ashley, Mavinic, & Koch. 2009. International Conference on Nutrient Recovery from Wastewater Streams. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283584918_International_Conference_on_Nutrient_Recovery_from_Wastewater_Streams_Vancouver_2009

Gilbert & Shapiro. 2013. Pigeons, Domestication of. Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. DOI10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2

Canova. 2005. Monuments to the Birds: Dovecotes and Pigeon Eating in the Land of Fields. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2005.5.2.50

Nicol. 1945. The Homing Ability of the Carrier Pigeon Its Value in Warfare. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4079708

I don't know why, but I loved this.