Holy smokes! The early history of tobacco

The perfect read over a long nicotine break

In my previous post on this topic we took a look at the basic principles of smoking, and how it delivers biologically active compounds to the bloodstream, and the history of smoking marijuana (Cannabis sativa), a broadly Eurasian pioneer plant which has been used within ritual contexts over the course of millennia by cultures located in areas as disparate as the Pamir mountains, the Central Asian steppes, the Middle-East and Eastern Europe.

As I already covered in this previous post how smoking worked, why some plants could be smoked with physiological effects, and speculated as to how these properties may have been discovered in the distant past of prehistory, I’ll move on right to the meat of this post’s topic: what is tobacco, the early history of its use, how did it evolve over time, and how did it come to become one of the most widespread drugs in the entire world?

The phylogenetic context

All tobacco plants are part of the genus Nicotiana, which is itself included in the family Solanaceae. This versatile family is known for possessing both very toxic members as well as excellent edible plants which are the staple of many diets today. While they are fairly global in distribution, the majority of the most useful Solanaceae (to humans) come from the Americas. The most toxic members, mostly European, include deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna), thorn apple (Datura stramonium) and Mediterranean mandrake (Mandragora officinarum). On the other hand, what would our dinner plates look like without the succulent tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) or the ever-versatile potato (Solanum tuberosum)?

Plant families tend to share life history traits that are more or less strongly expressed from one species to another. Here, clearly, one of these dominant traits is a super-active secondary metabolism, the biological process through which plants produce all the compounds that aren’t strictly necessary for survival, including pigments, alkaloids (which can be psychotropic or downright toxic) and volatile compounds which may have a pleasant or bad smell and taste.

The original function of plant alkaloids is to make them as unpalatable to herbivores as possible, by giving them a bad taste or causing harm to the aggressor, unfortunately things don’t always work out like that. The main active compound of tobacco, nicotine, is a natural insecticide which works by acting as an agonist (an activating partner) to the acetylcholine neuroreceptors. As these are the main receptors of the insect nervous system, exposure to high enough doses of the compound cause the system to go haywire. In humans, glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter receptor, so that the effect is different (although still toxic in high enough doses).1

The genus Nicotiana itself contains 86 species, the majority of which are found in Meso- and South America with other specimens present in the Pacific, Australia and one surprising African species endemic to Namibia, only recently added to the genus, and thus not represented on the old map below, Nicotiana africana. These plants are believed to have evolved in the Eastern Andes before spreading North, then West across the ocean before finally reaching Africa, landing on the continent from their foothold in Australia.2 How exactly this ocean-crossing occurred is still a matter of debate3 although since plants in this genus typically produce many minuscule seeds (<1mm diameter) per flower, there is a possibility of being transported on (or in!) the bodies of animals such as migrating birds or maybe even carried by strong winds or oceanic currents.

The plant itself

While most (if not all) members of the genus Nicotiana possess nicotine in their tissues, the amount that is present varies from species to species and based on environmental conditions. As the compound is originally a defense against grazing insects and other animals, the plant produces more during periods of stress which involve drought or damage to the plant. Out of the many wild species present throughout the world, only two would eventually see mass human usage: N. rustica and N. tabacum. This latter species would go on to become the main tobacco plant cultivated and smoked worldwide, making it the most important psychoactive plant on the planet. Both species are endemic to the Americas.

These tobacco species grow in tropical and subtropical climes, although on the right soil they are able to tolerate temperate conditions. They are annuals with a growth period of approximately 100 days with a preference for temperatures between 20° and 30°C and a humidity level around 85%. Exposure to frost may be fatal.4 Like many annuals, they prefer bare soil with no competition and can even become weeds spreading throughout disturbed habitats.

N. tabacum growing in Hawaii. Taken by Kim Starr.

Since the goal is to prevent fauna from feeding on its leaves, most of the plant’s nicotine is concentrated there, with a small minority found in the flowers and stem, and none in the seeds. It’s considered best to remove the floral buds and side-shoots during growth so tobacco invests all its energy in growing its large main leaves, and then hope for a dry period of several weeks before harvest for the leaves to mature and develop their aroma before being harvested.

Earliest traces

The history of tobacco’s domestication was very recently turned upside down by a discovery in the Great Salt Lake Desert of Utah, USA. The dry conditions are perfect for preserving biological material from decay and the passage of time. Archaeologists uncovered a dark patch of ashes surrounded by bird bones: this would prove to be the oldest camp fire ever found in the US, set up by hunter-gatherers of the Intermountain West’s Haskett culture. Allow me to set the scene.

It is a balmy summer evening. A group of hunters armed with obsidian and dacite-tipped spears and short stone knives return to their temporary camp for the night. They are near a pond, surrounded by untold miles of marshes and wetlands. If they are seeking the large game they’re known to pursue, maybe the pachyderms that still roam the continent, or herds of bovines, they have been disappointed so far, only managing to catch a deer, a few ducks and raid a nest for eggs. Still, a fire is lit out of willow branches, and the meat is cooked, while some busy themselves maintaining their stone tools, or knapping new ones. While waiting for the meal, or perhaps to relax afterwards, or even as part of a religious ritual of some kind, one of them reaches into a pouch. From it he pulls a large, sticky, fragrant leaf he collected days or weeks ago, when he was last in the mountains, a couple of days of travel to the North-East...

It may have been up to 12.300 years ago and probably a little earlier, not so late after the definite settling of North America, that the local people discovered the properties of tobacco (in this instance, N. attenuata, a more cold-tolerant species native to most of the Western United States). This is based on the finding within the preserved ancient bonfire, amidst the discarded bones of a well-earned meal, of four seeds of this species. It may sound insignificant, but within the context of the dig, there is a fairly high likelihood these were carried to the site purposefully, as the species is not adapted to the marshes of that region at the time, was not found in control samples outside the site, and is not eaten by the animals that would have been processed for food there. While the seeds do not contain nicotine, they are extremely small and could easily have been carried on the sticky glandular trichomes of the leaves when they were harvested. The authors can only speculate as to what was done with it, believing it may have been packed behind the bottom lip and chewed, or even smoked, a method that wouldn’t be attested by the archaeological record for another 9000 years.5

Afterwards the history of this product shifts southwards. Within “palaeo-Indian” times, long before 5000BC, there existed two wild species of Nicotiana in the Andes that attracted human attention (N. paniculata and N. undulata). These are believed to have been selectively bred and disseminated in an early act of plant domestication which eventually lead to the creation of a nicotine-rich species still cultivated today: N. rustica, which is the most potent cultivated tobacco. It’s theorised this plant was traded, spread and cultivated in the area, where it was used in a limited fashion for ritual and shamanistic purposes.6 The side effects of high nicotine intake (such as seen in a shamanistic context, typically preceded with fasting to accelerate body uptake) can include hallucinations, loss of colour vision, slowed heart rate, tremors, and eventually a catatonic state, particularly conducive to the symbolism of death and rebirth in the spirit world.7

This spiritual significance allowed it to extend its distribution until it reached Mexico, probably around 5000BC, where the ancestors of the Huichol Amerindians cultivated their own strains, reaching a powerful 18% nicotine level. From there it continued ever northwards, reaching the Mississippi basin between 2000 and 1000BC, until eventually by 1000AD it was cultivated on most of the Eastern seabord and parts of the American Southwest. Even groups of hunter-gatherers and those who relied on fishing to survive were known to plant and tend tobacco, regardless of affinity with other domesticated crops. One of the main theories is that nicotine addiction by shamans may have been an important driver of the plant’s spread, as individuals in marginal areas of distribution may have sought to secure better supplies. [6 again]

Its cousin N. tabacum, the species commercially grown to produce tobacco worldwide today, followed a different trajectory. As N. rustica is drought adapted, it’s unsuitable to grow in the humid conditions of South America’s lowlands. Consequently, N. tabacum was domesticated at an unknown later date and spread eastwards through the Amazon basin, where it filled the void left by the other species’ absence. It eventually reached a maximum area of distribution also encompassing Central America and the Caribbean, ending up North all the way to Southern Texas and Arizona. While less potent, this species has a smoother taste which makes smoking more palatable. Even today, the Huichol, Zuni and Navajo native groups prefer this commercial tobacco for social and everyday use, reserving N. rustica for ritual occasions. [still 6]

Pre-Colombian tobacco in North America

Besides the exceptional find in Utah, most of the evidence of ancient tobacco use in North America comes from gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis which is able to find preserved alkaloids such as nicotine inside well-preserved stone pipes (referred to as “medicine tubes”). A recent study found nicotine in an ornate tube carved of limestone unearthed from the Flint river, a tributary of the river Tennessee. The Flint river site is a shell mound 3 metres tall that was formed by deposits over the course of 1200 years starting in 2200BC. This area was a base of operation for local hunter-gatherers for centuries, and contains a wealth of archaeological items besides medicine pipes, including atlatl weights, fishhooks and axes. Inside the pipe, found in a strata dated to 1685-1530 BC, residues of nicotine several millenia old could still be found. Unfortunately the analysis cannot ascertain which species of tobacco produced the nicotine, but as stated above the Mississippi basin is considered to be the earliest point of entry of N. rustica into North America. Thus, it’s debatable whether this is from an early adoption of the cultigen, or a wild species indigenous to the region.8

Further smoking pipes, found with residues of soot and nicotine inside, were unearthed in the North-Eastern region of America dating to 500BC, in a continuation of the find from the Flint river. These were often found associated with burials and mounds, forming a continuous time series up until European contact in the region, and beyond. Many of the earliest finds are simple tubes, as pictured above, and it has been argued that some of them had alternate functions such as sucking tubes or even pigment sprayers. However, the detection of soot and nicotine remains on the inside removes any ambiguities, for a portion of the specimens at least. Later designs include “platform pipes” also pictured above, mainly found in the Ohio region and sometimes formed of unusual stone that would have been obtained through long-range trade networks. Later pipe designs involved simple clay or wood “elbow” pipes, or complex effigies which may have been related to spirits of divinities.9

Pipe smoking also has a long time continuity in the American Plateau (situated in the Pacific Northwest region, straddling the American and Canadian border). While previously described as a colonial European import from the Eastern coast in the early 19th century, molecular analysis of stone pipe remains showed traces of nicotine going back to 800 AD in the region. Based on current chronology of the spread of tobacco cultivation, it’s believed the inhabitants of the region may have used indigenous species such as N. attenuata or N. quadrivalvis, contradicting early ethnographic work claiming bear-berry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) was the only plant used for inhalation before European contact. This impression may have been caused by the fact that indigenous tobacco species are indeed rare in the area, and the climate is not conducive to the growing of domesticated tobacco. It should be noted however that up to 50 other plants with aromatic properties were smoked by various groups of the region, bear-berry chief among them, alone, in combination, or mixed with tobacco. Thus, findings of pipes do not automatically correlate with tobacco usage, and if possible, biomolecular analysis must be carried out before any conclusions can be drawn.10

Southern Pre-Colombian consumption (and a bit about Post-Colombian too)

In Meso- and South America, while there are some allusions to the Olmecs (1200-400BC) making use of tobacco (which would make sense considering the antiquity of the plant’s domestication), direct references in the litterature are hard to find. Most papers focus on the far better documented Maya, Inca and Aztecs, as these were closer in time to, or contemporaneous with, the presence of European chroniclers who recorded their practices. Thus, paradoxically, while these areas are certainly the ones with the most ancient presence and usage of domesticated tobacco, there is little archaeological record to draw from, leading to a seemingly relatively recent usage of tobacco compared to the Northern continent.

One possible exception to this is finds of human effigies of the Colima shaft-and-chamber tomb phase (100BC-200AD) in Mexico. These show seated humans with their head reclined backwards using “snuffers”, tube shaped contraptions through which powder could be funnelled to the nose. There is no certitude whether this powder was the tobacco snuff we are familiar with, but it’s a possibility, as the Inca are known to have snuffed tobacco.11 The Aztecs also had their own specific word for powdered tobacco, “piciete”.

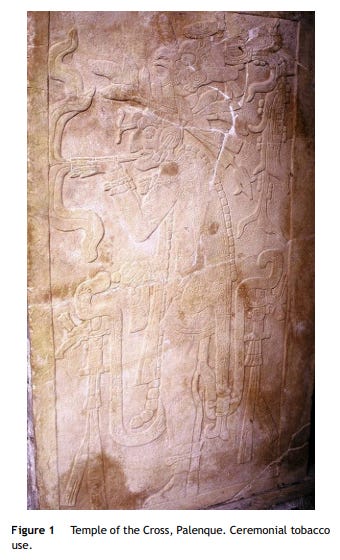

The Maya (250-1697AD for the classic and post classic periods) consumed a liquid called “balché” in order to gain prophetic powers, which was accompanied by the smoking of N. rustica (which they called “piziet”) to enhance its effect. Tobacco was also added to other alcoholic drinks to increase their potency.12 Meanwhile for the Aztecs, tobacco was considered powerfully medicinal against a range of issues (asthma, syphilis, headaches, arrow poisoning). Members of the influent merchant class also used the plant in social and ritual situations such as welcoming rituals and as offerings, often combined with cocoa and flowers. After a meal, the Aztec emperors at the time of the Spanish chronicles smoked tobacco in a cigar, flavoured with the fragrant gum of a tree of the Liquidambar genus.13

The areas that were occupied by the Spanish, primarily central America and the Caribbean, all had dominant traditions of cigar and cigarette smoking, hence these habits being imported to Europe preferentially over the practice of pipe smoking, which, while present in the new world colonies, was considered absolutely marginal in as late as in 18th century testimonies, only used by natives and Africans, although Spaniards seeking relief from asthma also used them.14

Conclusion

Tobacco is clearly a plant that left no one indifferent, attracting the attention of some of the earliest humans to come across it in the beautiful American continent and becoming one of the earliest plants domesticated there, eventually spreading even to people that didn’t practice agriculture. Whether it be a wild species or a cultigen, taken alone or mixed with other powerful psychotropics, chewed, sniffed, drunk or smoked, it held a vital place within nearly all the cultures of the American people, before and after European contact. This is far from the end of this plant’s extraordinary journey, but that’s a tale for another time…

Millar & Denholm. 2007. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: targets for commercially

important insecticides. Invert Neurosci 7:53–66. DOI 10.1007/s10158-006-0040-0

Marlin D, Nicolson SW, Yusuf AA, Stevenson PC, Heyman HM, Krüger K (2014) The Only African Wild Tobacco, Nicotiana africana: Alkaloid Content and the Effect of Herbivory. PLoS ONE 9(7): e102661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102661

: Wylie, S.; Li, H. Historical and Scientific Evidence for the Origin and Cultural Importance to Australia’s First-Nations Peoples of the Laboratory Accession of Nicotiana benthamiana, a Model for Plant Virology. Viruses 2022, 14, 771. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14040771

https://www.fao.org/land-water/databases-and-software/crop-information/tobacco/en/

Duke, D., Wohlgemuth, E., Adams, K.R. et al. Earliest evidence for human use of tobacco in the Pleistocene Americas. Nat Hum Behav 6, 183–192 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01202-9

Winter, JC. Tobacco Use by Native North Americans - Sacred Smoke and Silent Killer. 2000. UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA PRESS. p. 324-326.

https://www/europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/magical-mystical-and-medicinal/tobacco

S. Carmody, J. Davis, S. Tadi, J.S. Sharp, R.K. Hunt, J. Russ, Evidence of tobacco from a Late Archaic smoking tube recovered from the Flint River site in southeastern North America, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Volume 21, 2018, Pages 904-910, ISSN 2352-409X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.05.013.

Rafferty, S. Chapter 2: Smoking Pipes of Eastern North America. 2016. E.A. Bollwerk, S. Tushingham (eds.), Perspectives on the Archaeology of Pipes, Tobacco and other Smoke Plants in the Ancient Americas, Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-23552-3_2

Tushingham, Snyder, Brownstein, Gang. Biomolecular archaeology reveals ancient origins of indigenous tobacco smoking in North American Plateau. 2018. PNAS. 115 (46) 11742-11747. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813796115

Furst P. ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR SNUFFING IN PREHISPANIC MEXICO. 1974. Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University, Vol. 24, No. 1 (July 31, 1974), pp. 1-7, 9-28

Carod-Artal F.J. Hallucinogenic drugs in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures. 2011. Neurología. 2015;30(1):42—49

Elferink J. THE NARCOTIC AND HALLUCINOGENIC USE OF TOBACCO IN PRE-COLUMBIAN CENTRAL AMERICA. 1983. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 7 (1983) 111-122

Shaw T. Early Smoking Pipes: In Africa, Europe, and America. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland , Jul. - Dec., 1960, Vol. 90, No. 2 (Jul. - Dec., 1960), pp. 272-305

Good essay. I was an archeologist for a time (it was my major) and most of my field experience was with California Bay Area sites. They were hunter gatherers, subsisting mostly on acorns (our native oaks produce more nutritious acorns than European varieties) but the one plant they did cultivate was tobacco. There’s lots of debate about why they didn’t deliberately grow other staple food plants since they obviously knew how considering all the tabaco they grew. They would combine it with crushed shells to increase the potency.

>These plants are believed to have evolved in the Eastern Andes before spreading North, then West across the ocean before finally reaching Africa, landing on the continent from their foothold in Australia. How exactly this ocean-crossing occurred is still a matter of debate

Fascinating!

The third citation puts forth a conundrum on dating: "Bally and colleagues placed the mutation event of NbRdr1 to NbRdr1m at 710–880 thousand years BP [37], long before humans occupied the continent 65,000 years BP [9]. If this were the case, it seems distribution of the allele either has not spread beyond the region it first occurred in or has shrunk to this region from a broader distribution over this vast time period."

I don't know that much about plant genetics, but is it possible that this highly diverged mutation is from the Americas, and arrived as you suggest? Then the American Nicotiana crossed with the local variety.