Bullets with butterfly wings: nature conservation and the military

It turns out that a thousand flowers bloom after the passing of tank treads

Introduction

While the military is often green in a literal sense, they’re rarely considered to be eco-friendly, in whatever meaning of the term one wishes to apply. Even in peacetime there’s precious little room in their critical and dangerous missions for caring about the natural world around them, to say nothing of the incredibly gasoline-thirsty machines they regularly use for training. There’s no way to drive through grasslands in tanks and troop transports, or firing off mortars, rockets and bullets in the training grounds, without causing a trail of devastation that’d leave the most seasoned lumberjacks or construction crews dumbstruck. Yet, being turned into a military base or training ground is one of the best things that can happen to a patch of nature, at least in the Western world. Join me behind the barbed-wire fences and warning signs of military bases and conflict zones renowned for their rich biodiversity to learn how this could be the case.

The basics: Palearctic temperate ecosystem dynamics

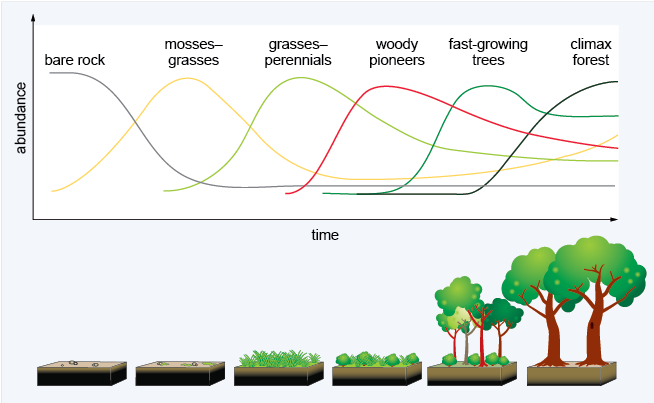

One of the most fundamental dichotomies in ecology is that between “open” and “closed” canopy ecosystems. The former are those where the sun is able to shine fully on all the vegetation (grasslands, heathlands, deserts, coastal dunes, alpine highlands) whereas the latter includes areas with dense cover that blocks out a significant portion of sunlight (all kinds of forests, mainly). The two types exist in an equilibrium that depends on many factors: climate, geology, soil fertility, topology, and ecological dynamics (often fauna-dependent). In most cases, a completely open area will be subject to ecological succession, wherein various plant species will sprout and grow over time. First come the pioneers, usually tiny annual plants that can grow in extreme conditions (dry and poor soils, full sun exposure) and are quickly crowded out. Then come grasses, taller annuals and perennials, slowly colonising every piece of bare soil until there’s an uninterrupted layer of vegetation covering the ground. Finally, the woody plants arrive, with their own procession of sunlight or shade adapted shrubs and trees.

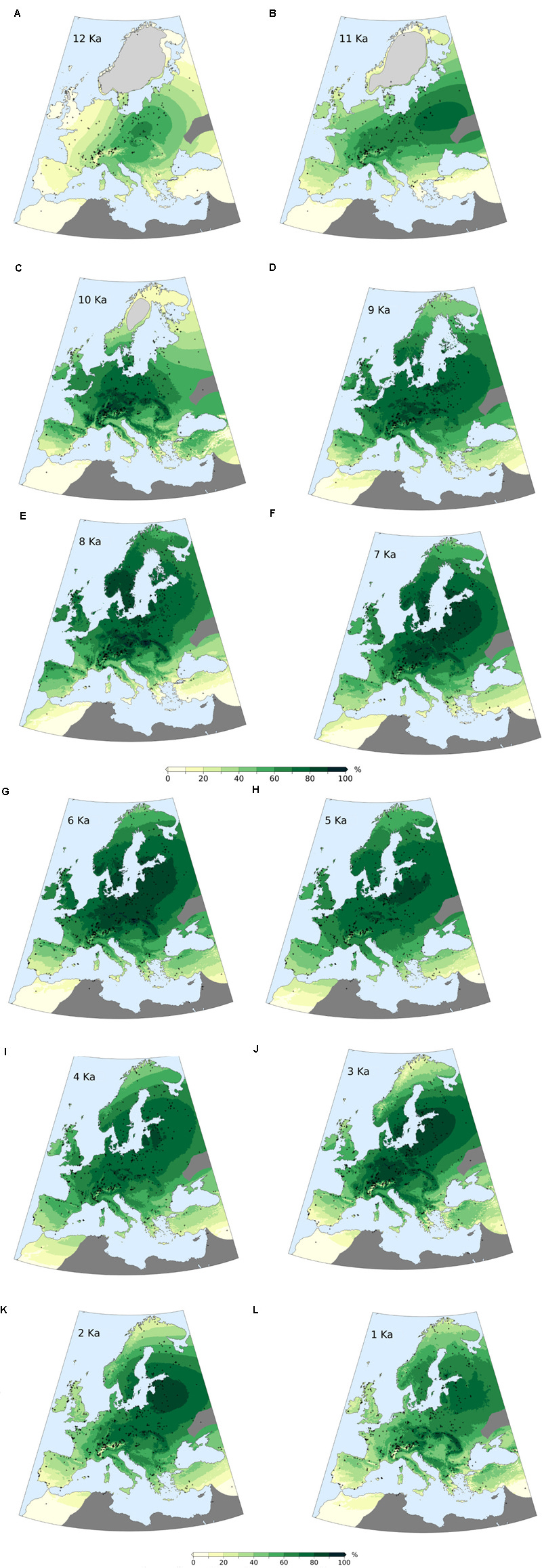

In Europe, this phenomenon was once balanced out by the climate as well as the presence of abundant megafauna (various definitions but just imagine anything bigger than a roe deer) that grazed and trampled the grasses, shrubs and saplings, churning the soil enough that there was turnover, creating ever-evolving patchworks of open and closed habitat depending on herd movements, weather, season and other such factors. During the last glacial maximum (about 20,000 years ago), most of Western Eurasia was so inhospitable it was devoid of trees, comprised either of ice sheets or mammoth steppe, an endless plain of grasses, small herbaceous plants and a few hardy shrubs that were grazed by herds of animals. The mammoths disappear from the continent after this time period, then during the warming period between 12,000 and 6,000 years ago, forests burst forth all over Europe, in large part due to the arrival of a warmer and wetter climate. After a peak in forest cover 6,000 years ago, open areas start returning to Europe, at least in part because of the Neolithic revolution and Human activity. 1

This dynamic ensured that a very wide variety of organisms are adapted to open environments in Eurasia, and indeed in the micro scale the biodiversity of temperate grasslands rivals that of tropical rainforests2. Be it plants, insects, mammals or birds, a high proportion of our species require open ecosystems to survive. During periods with more open areas in Europe they thrived, and during periods of intensive forest growth they retreated to the Eurasian steppe to the East or scrubby areas around the Mediterranean. The Neolithic revolution and the flourishing of civilisation across Europe over the ensuing millennia allowed those species to return by adopting pastures and cereal fields instead of the open steppe, and nest in hedgerows instead of scrub. Less intensively-managed open ecosystems were maintained on a wider scale, further away from human habitation, by itinerant pastoralism.3

This dynamic was particularly disrupted in the second half of the 20th century with the mass adoption of tractors, followed a couple of decades later by the introduction of synthetic fertiliser and pesticides. Wetlands were drained, grass meadows were enriched, harvested sooner and became dominated by dense and fast-growing grasses, hedgerows were ripped up to create bigger fields, which were then regularly sprayed with weed-killer and insecticides, and harvests became far more sudden and left no time for animals to escape danger, crushing nests indiscriminately. The results of this shift in policy, while certainly effective at their stated goals of increasing agricultural output, are plain for all to see: open-field bird species are in free fall across much of Western Europe4, insects have significantly declined across many clades, pollinators chief among them5, and the less competitive or resilient plant species vanished from field margins and pastures.

There are vanishingly few areas that escaped the initial phases of this mass modernisation of agriculture. Some of the largest ones, in Europe, were military encampments.

Little green men

Military training areas have multiple needs: permanent or temporary housing for staff, as well as space for all the logistical and technical operations needed to run the base and storage for machinery and equipment, are some of the most obvious ones. What they also require is lots of empty space in which to conduct physical training, weapons drills and training exercises far from prying eyes, with lots of open ground for tanks and other machines to drive around. To this end, particularly remote, unproductive and uninhabited areas (which often translates to areas with naturally poor or dry soils such as heath lands, which are cheap because mostly unusable) were acquired or requisitioned by Europe’s armies, especially starting in the 19th century. Below are a few examples:

The French armed forces own 250,000 hectares of land, 200,000 of which are under at least one biodiversity protection statute. In total, 20% of this land belongs to the Natura 2000 network that harbors ecosystems and species which are endangered and ecologically significant at the EU level. For comparison, 13% of French metropolitan land as a whole is under Natura 2000 statute, meaning military bases are significantly more likely to contain sensitive species.6

The UK’s 190,000 hectares of military estates are home to 70,000 hectares of nature conservation sites and 40,000 hectares of national parks (unclear if there’s overlap or not) and contain numerous rare or even unique species for the country. Of these sites, 150 are considered sites of special scientific interest (SSSI).7

Numbers for the Netherlands are slightly trickier to obtain, but it appears to be around 26,000 hectares currently, with 17,000 managed as nature reserves and 15,000 being part of the Natura 2000 network (again, the exact overlap is unclear).8

Of Belgium’s approximately 26,000 hectares of military bases, 19,500 are considered eligible to enter the Natura 2000 network.9

Even the US armed forces, which one would expect to be more focused on warfighting than managing the greenery, as the largest army in the world, have Integrated Natural Resources Management Plans (INRMPs) across 148 of their installations, and recognise the high biodiversity contained within many of its bases.10

This translates into remote areas of Western countries hiding bases covering tens, hundreds or even thousands of square kilometres comprised of mostly open land on marginal soils that have rarely been treated with fertilisers, and contains a dynamically shifting environment where live-fire drills cause fires that clear the land, mortar and bomb craters become temporary ponds and tank tracks churn up the soil, breaking up the layer of grasses to give smaller flowering plants a chance.

Habitats and species of military bases

The Valbonne military base of the Ain region of France was recently spotlighted in a LIFE program specifically targeting military installations for nature restoration. This camp was created in 1872 in what was then the Valbonne plain, and currently occupies about 1600 hectares (10 sq miles). While the rest of the plain was gradually transformed into ordinary agricultural land, the presence of many horses grazing the vegetation until the world wars and the lack of human land use allowed the base to retain its original ecosystem: one of the few dry steppe grasslands left of France. This rare habitat of nutrient-poor and moisture-deprived soils contains over a quarter of France’s protected plant species and is also the ideal home for many specialist insect species and even a few endangered birds, such as the lesser bustard (Tetrax tetrax)11.

This typically Eurasian ground bird depends on extensive and traditional farmlands with a mix of low-intensity and diversified crops, and low-density cattle grazing, the landscape being divided by hedgerows and the like. Over the past century it went extinct in 15 countries and experienced one of the most precipitous declines of any European countryside bird12. Its current strongholds are in central Spain, small spots in France such as Valbonne and nature reserves in the Netherlands, as well as more broadly Sardinia, the Balkans, Caucasus and central Asia. Its decline is attributed to habitat degradation, insect decline, increased disturbances in its nesting areas and hunting. By taking measures to protect a species so ecologically demanding and sensitive, there are ripple effects that preserve many other lesser known or less exigent species that also thrive in the types of habitats the lesser bustard needs. This is known as the umbrella species concept. In Valbonne, this habitat restoration included among other things mechanical destruction of scrub and small trees that were colonising the steppe, followed by a program of itinerant pastoralism throughout the base with donkeys, cows and goats in order to keep future growth in check and restore the old habitat dynamics.13

Meanwhile, the Salisbury Plain training area, in Wiltshire (UK) covers 150 sq miles, 103 of which are rented to farmers for grazing or crops, with 47 kept as a training area for live-firing exercises. Established in 1898, it covers a chalk plateau whose grasslands are particularly rich in flowering plant species14, and contain many other species such as insects and birds. One particular star of the area is the great bustard (Otis tarda), which went extinct in the UK in the 19th century because of land-use change and hunting, but was reintroduced to the Salisbury plain in 2004, with a current small population of a little over a hundred animals, reportedly breeding at replacement level.15

This impressive animal is the heaviest flying bird in Europe. Its distribution is very similar to that of the lesser bustard, as are its ecological preferences and global distribution. The species is considered endangered with around 30,000 with an enormous decline of 1/3 of its estimated global population in 11 years16. Currently surviving in the plain, these animals are a topic of much interest for passing tourists, with the Great Bustard Group (who reintroduced the species) organising multiple daily safaris around the edges of the military base to see the birds.

Fort Bragg is one of the most famous military bases in the USA, housing among others the US army special operations command and two airfields. At 251 sq miles it dwarfs the other installations discussed here (which makes sense since land is one thing America isn’t lacking), but was only created in 1918. After a fraught period where the base’s activities were strongly disrupted by obligations to protect the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis), a fruitful collaboration with nature conservationists led to the cordoning off of sensitive areas and the creation of restrictions that allowed military training to coexist with the bird, whose population finally increased over the years (to the point the base had the second largest population in the world in 2016, according to ft. Bragg spokespeople), which allowed for these restrictions to be relaxed17. It seems to have become something of a mascot or running joke on the base: “You really love this bird - except for when you really hate this bird”18. Extremely rare butterfly species, St Francis's satyrs (Neonympha mitchellii francisci), associated with forests and wetlands regularly cleared by fires (such as those caused by artillery training) also live in the base, risking death from the regular bombardments but depending on the habitat to survive.19

Finally, it’s impossible to mention military nature conservation without bringing up the quite famous, but entirely accidental, ecological miracle of the Korean peninsula’s demilitarized zone (DMZ), which runs longitudinally across the peninsula, along the borders of the two countries. Covering 907 km², it’s a ribbon approximately 2.5 miles across that’s bracketed by walls, barbed wire, bunkers and other military installations, and filled with mines. Civilian access is strictly monitored, and frequently forbidden, and as such no development whatsoever has taken place there since the armistice of 1953. At present, it harbors over a third of South Korea’s endangered species, and a similar proportion of its overall fauna and flora species. This richness is attributed to the lack of human land use, allowing natural forest habitats to develop, but also the diversity of habitats between both ends of this strip of forbidden land over 150 miles long, encompassing wetlands, rivers, forests and mountains.2021

Conclusion

In the end it does seem that opposites attract, and that people whose role is preparing for war and death often end up nurturing fantastic biodiversity around them. Whether accidental or deliberate, the biodiversity of these military bases shows that when history, practicality and ecology come together, great things can happen, and unique habitats and species are able to thrive where they’d otherwise have disappeared generations ago.